Incorporating Kleros in Long-Term Energy Supply Contracts

This report was written and produced by Abeer Sharma as part of the Kleros Fellowship regarding the incorporation of Kleros in long-term energy supply contracts.

This report was written and produced by Abeer Sharma as part of the Kleros Fellowship of Justice Program.

All referenced footnotes can be found at the bottom of the article.

ABSTRACT

Long-term contracts are a special category of contracts where the obligations of the contracting parties are spread over many years – sometimes up to decades. While used in a range of different transactions, they are most famously used in lucrative supply contracts in primary resource industries such as coal mining, liquified natural gas, electricity, and nuclear power supply contracts.

Contracts in these energy industries can last for decades due to the high capital investment and operating costs required to be a buyer or seller. However, nobody can anticipate how economic or geopolitical changes will disrupt the commercial balance of these transactions. A price negotiated at the start of the relationship may become too onerous for a party after 10 years. The sheer scale of operations and the crucial nature of the product being supplied makes it undesirable to terminate the relationship once either party breaches its contractual obligations due to external pressures. Contracting parties therefore insert price review mechanisms (also known as market reopener clauses) to provide some flexibility in their continuing transactions.

Price review mechanisms give parties an opportunity to first adapt their contract by amicably agreeing to alter the price paid or quantity supplied. In case they cannot amicably resolve their differences, the failed negotiations are treated like a dispute and referred to binding adjudication by courts or (more commonly) arbitral tribunals.

However, relying on judges or arbitrators to essentially renegotiate the contract and arrive at a new commercial balance has faced criticism by several commentators, as the job of these adjudicators is ultimately to settle legal disputes and there are few if any questions of rights and obligations in most price review disputes. Judges and arbitrators can also be criticized on the grounds that they might not be able to render an objectively ‘fair’ decision that reflects the relevant socioeconomic state of affairs.

This paper explores the viability of adopting Kleros’ Oracle and Escrow use cases as an alternative settle price review disputes. It is structured as follows:

Part I provides an introduction for long-term contracts in the energy supply industries, explaining their rationale and usage.

Part II details how a market reopener clause functions, describing the relevance of trigger criteria, amicable settlement procedures, and the objectives behind selecting a binding adjudicatory procedures to finally settle the dispute.

Part III highlights the three major options available to parties for obtaining an adjudicatory judgment over their price review dispute – expert determination, litigation, and arbitration. It explains that arbitration is generally the preferred method for settling such disputes.

Part IV critiques the use of arbitration as the preferred price review dispute settlement process, noting certain shortcomings and weaknesses in its structure and implementation.

Part V proposes and evaluates the use of Kleros as a potentially viable replacement for arbitration as the ideal means for settling price review disputes.

Part VI concludes the paper with a discussion of the obstacles that must be navigated and the concerns that must be addressed before Kleros can be practicably implemented in price review disputes arising out of long-term energy supply contracts.

I. INTRODUCING LONG-TERM ENERGY SUPPLY CONTRACTS

The purpose of a written contract is to evidence a legally enforceable agreement between contracting parties. The contract reflects the mutual intention of the parties, serving as a reminder as to what they had agreed to do or refrain from doing when they had entered into their relationship.

The document acts as a tool to explicitly delineate the rights and obligations of the signatories and is useful in case any disagreement or dispute arises regarding these rights and obligations. Without a written contract, the whole dispute devolves into a ‘he-said, she-said’ situation and a wronged party is left without any remedy. (1)

It is thus a wise idea for parties contracting in good faith(27) to carefully comb over the details of their contract to ensure that the text of the contract adequately reflects their mutual intentions and factors in any potential loophole or change of circumstances that may upset the existing commercial balance.

However, no contract can ever envision every single factor or occurrence that can affect the relationship between the parties, even if the document runs into thousands of pages. Even the most cautious of parties cannot anticipate every unforeseen event that will affect their future conduct. This vulnerability is especially pronounced in the case of long-term contracts.

Long-term contracts represent commercial relationships where the contractual obligations performed by the parties are spread over many years (ofttimes up to decades). These contracts are used in a variety of transactions, but are most famously found in supply contracts used in primary resource industries such as the electricity wholesaling(2), coal mining(3), and oil and gas industries.(4,5)

The seller in such a transaction is usually a producer who supplies the energy resource and the buyer is a “middleman” that processes, stores, and/or distributes the resource onwards to its own buyers. The number of buyers and sellers in the industry is uncompetitively small.

For example, in long term liquified natural gas (LNG) contracts, the seller is either a global conglomerate (like Royal Dutch Shell, the largest gas producer in the world(6)) or a state-owned entity (such as Gazprom in Russia) that is responsible for producing the natural gas. These sellers have a natural monopoly over the reservoirs that they produce natural gas from, as the resource can only be commercially extracted from limited areas where it is physically present in large quantities. Similarly, the buyers of gas may range from multinational corporations (Royal Dutch Shell is again one such entity) to government subdivisions (eg Kogas in South Korea).

These buyers tend to be gas wholesalers that store and supply gas to the relevant end-user market, for the purpose of which they have an official or de facto regional or national monopoly. It can thus be deduced that the existence and identity of buyers and sellers is overwhelmingly contingent upon geography.

It is in each party’s interest to ensure that the relationship lasts as long as possible, as both incur massive upfront capital investments in order to lay down the necessary infrastructure to carry out their respective duties. For instance, in the US Oil & Gas sector, the average cost of developing a gas field may cost up to billions of dollars. The investment can only be recouped if significant sales are made. It is therefore in the seller’s best interest to ensure that the buyer commits to the transaction for a long period of time. Finding a new buyer may be difficult or even impossible, as it may require the establishment of new pipelines or shipping routes and the overhaul of the entire supply chain.

Indeed, this is why ‘take-or-pay’ provisions are commonly utilized in such contracts. A ‘take-or-pay’ clause imposes upon the buyer an obligation to continue paying the seller for the product even in instances where it is unfeasible or undesirable for the buyer to receive it (eg the buyer may be having logistical difficulties in its processing site or its storage facilities may be full due to low demand in the end-user market). The specifics of these clauses are heavily negotiated, and may involve provisions for a discounted rate where the buyer does not actually take the product.(7)

The buyer will similarly have invested a fortune in building up its infrastructure to store and distribute the product. Just as importantly, its own customer base may involve a large number of end-users such as businesses or households that will expect a steady supply of energy for years. This is the reason that Vattenfall – the Swedish state-owned power utility – enters into long-term supply contracts with foreign nuclear power manufacturers.(8)

With a long-term commercial relationship in mind, the initial contract price is negotiated to ensure that the seller attains an adequate profit over the lifetime of the contract without being too cumbersome on the buyer. The price is paid out periodically – typically monthly(9) - and may include various other terms and conditions such as the ‘take-or-pay’ clause mentioned above. Because the seller has security of revenue, it can charge smaller profit margins for every installment. A steady price also provides end-users on the buyer’s side the benefits of predictability, allowing them to accurately budget their finances.(10)

However, no reasonable party can expect prices to remain constant over 20 years. Long-term energy supply contracts may have their existing commercial balance destabilized in several ways. These may include:- (11,12)

Inflation risk

Generally, the parties will anticipate all reasonable inflationary/deflationary pressures in their pricing clause. They may, for instance, opt to peg the payable contract price to a mutually acceptable measure of inflation. Doing so usually nullifies inflation risk, although it may be possible that the accuracy of the relevant inflation index is eventually challenged for some reason (eg if the relevant authority responsible for publishing the index changes its measurement methodology).(13)

Operational risk

Something may go wrong during the day-to-day operations of either party. For instance, the seller’s drilling machinery may break down and require replacement. Or perhaps there may be a labour strike that shuts down the buyer’s storage facilities.

Demand risk

The end-user market on the buyer’s end may not exhibit high enough demand for the product. This may happen for several reasons, such as the increased availability of alternative fuels or technological developments that render machinery more energy efficient.

In such a scenario, the buyer cannot profitably sell off the supply it has purchased and has to store it or let it go to waste; continuing the contract under the initial terms will place the buyer under financial stress. Conversely, maybe demand in the end-user market skyrockets and the existing supply has to be increased proportionately – something that may impose higher operating costs on the seller.

Supply risk

There may occur a previously-unanticipated glut in the market for the product being supplied. This may be due to the entry of new competitors or the discovery of new production sources (not under the control of the seller). Such an event may render breaching the contract and dealing with its consequent fallout a more financially sound choice for the buyer over continuing the relationship under the initially-agreed price. (14)

Political and Regulatory risk

There may be a change in relevant laws, policies, or regulations that throws the relationship under disarray. For instance, a new protectionist government may be elected in the buyer’s country which dislikes importing energy from foreign suppliers and imposes strict import quotas.

Perhaps the seller may be subject to new, stringent environmental regulations that increase its cost of production. Maybe the product is routed through a third country via pipelines or rail (in cases where the buyer and seller are very far apart) and the third country charges higher tariffs or imposes restrictions on how the product can be transferred through its borders. In all such cases, the cost of the transaction will change substantially for either or both parties.

Risks such as these may destroy the contract if one or more parties are unable to perform as per the original terms. In some cases, a rigid price may even foster resentment in a disadvantaged contracting party and encourage it to scrutinize the contract or the other party’s performance, raising objections or searching for grounds of termination.(15)

It is thus necessary for parties to ensure some flexibility in their long-term commercial relationship. This is why long-term contracts in the energy sector generally incorporate a price review mechanism.

II. ANATOMY OF A MARKET REOPENER CLAUSE

‘Contract adaptation clauses’ essentially provide for the adjustment of one or more terms in a contract in order to restore the commercial balance between the contracting parties.(16)

In particularly sophisticated, high-value long-term contracts, the payable price need not be defined as a specific number. Instead, it may be set out as a sophisticated formula, depending on the nature of the commodity, practices of the relevant industry, and characteristics of the parties. For example, in the coal industry, ‘the most common pricing mechanism includes a fixed “base price” that will remain in effect from the time of formation through an initial term or period, followed by subsequent periodic adjustments to that base price…’ (17)

Similarly, the LNG industry tends to have a rather diverse set of pricing formulas. In some regions where there is a competitive gas market of suitable liquidity - known as a gas trading hub (18)

The parties may agree to base their contract price on the monthly average price of gas traded in the hub, while making certain allowances to account for different economic conditions in the seller and buyer’s respective domestic markets (as it is not necessary that either or both parties actually be located close to the hub). (19)

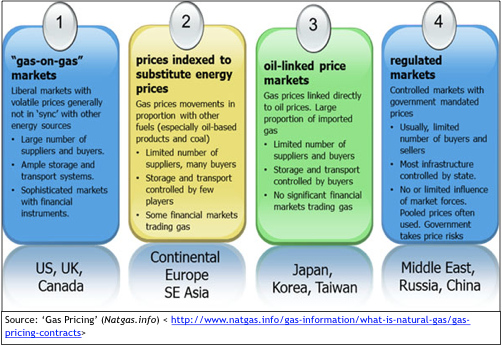

In case the buyer and/or seller are too far away from an LNG trading hub, or where the use of one for pricing their contract has otherwise been deemed undesirable,(20) the LNG contract price may be pegged to the market rates of a close substitute fuel (such as coal or oil) under the assumption that the price of gas would closely follow the trends of the substitute fuels. In practice, LNG supply contract pricing mechanisms exist in one of four groupings, depending on the region:

Regardless of the specific formula used or the industry concerned, ‘price review mechanisms’ or ‘market-reopener clauses’ are a subset of contract adaptation clauses; they allow a contracting party to request an adjustment to the periodically-payable contract price and/or the volume of the relevant product supplied upon the fulfilment of certain ‘trigger criteria.’

Trigger criteria

The applicable trigger criteria can vary depending on the industry and parties. There might be a provision where a market reopener clause will be triggered automatically upon the passing of a set amount of time (Such as bi-annually, every 5 years, etc.). (21)

Similarly, a price change may be triggered by a major change in some index that the contract price is pegged to (such as the price of competitive/substitute fuels). (22) In some exceptional cases, contracts may provide for ‘joker’ or ‘wildcard’ review clauses where a party has a limited number of opportunities to request a price review unilaterally.(23)

More elaborate trigger mechanisms may allow for price review upon the fulfilment of certain external criteria, especially ‘upon a showing of such things as a “gross inequity” or an “economic hardship” or the occurrence of an “unforeseen” or “unforeseeable” event.’(24) These unforeseeable events may encapsulate a wide range of scenarios.

For instance, a supplier may trigger a price review if its costs of production exceed the contract price. A buyer may invoke the market re-opener clause if new government regulations in the end-user market strictly limit how much of the product it can sell to end-users.

This is why wise contracting practice is to draft an intentionally vague price review clause in order to include trigger events or circumstances that are not anticipaple. For example, one famous long-term LNG contract laid out its applicable trigger criteria as follows: (25)

If at any time either party considers that economic circumstances in Spain beyond the control of the parties… have substantially changed as compared to what it reasonably expected when entering into this Contract ... and the Contract Price ... does not reflect the value of Natural Gas in the Buyer's end user market… "

It further went on to clarify what factors would mandatorily (although not exhaustively) be included in determining whether or not the trigger criteria were satisfied:

In reviewing the Contract Price in accordance with a request pursuant to [the clause above] the Parties shall take into account levels and trends in price of supplies of LNG and Natural Gas [redacted] such supplies being sold under commercial contracts currently in force on arm’s length terms, and having due regard to all characteristics of such supplies (including, but not limited to quality, quantity, interruptability, flexibility of deliveries and term of supply).

This vague wording can sometimes be a double-edged sword. While it is undoubtedly beneficial in the sense that it is flexible, it can also be a source of disagreement between the contracting parties. For instance, while one party may claim that a significant change of circumstances requires an adaptation of the contract price, the other party may reject that contention by claiming, inter alia: (26)

- That no change of circumstances has happened in the first place.

- That a change of circumstances may have happened, but it is not ‘significant’ or ‘substantial’ enough to merit a price review

- The changed circumstances were ‘foreseeable’ or ‘reasonably expected’ at the time of contracting, thus already being factored in by the initial price.

- The asserted change does not fall under the ambit of the price review mechanism. For instance, some contracts may require that the changes must be ‘changes in economic circumstances’. In such a case, the parties may disagree as to whether the changed circumstances under contention are truly ‘economic’ in nature.

- That the asserted change in circumstances was actually under the control of the requesting party, and the latter has in some way been responsible for or contributed to their existence.

- The rejecting party may disagree with the variables or factors that the requesting party used to come to its conclusion that the contract price needs to be reviewed.

- That the requesting party’s calculation of the hardship it is facing is incorrect.

Because of this, market reopener clauses typically detail a procedure through which any disagreements or contentions regarding the contract price may be resolved.

Amicable Settlement Procedure

The complexity of the procedure for reviewing the price may vary from contract to contract. In general, higher value contracts will have a much more cumbersome procedure than lower value contracts. The party requesting a price review will typically have to send a notice letter to the counterparty, informing the latter of its desire to revise the price.

Since the counterparty is naturally expected to be unwilling to accept terms less favourable to it than under status quo, the parties have a mutual obligation to amicably settle on new terms. The contract may even prescribe how exactly they are required to arrive at a settlement: The parties will usually undertake structured negotiations or in some cases opt for mediation. Regardless of the specific method used, the parties must strive to settle their disagreements in good faith.

Of course, given the high risk/high reward nature of investing in primary resource industries – especially where long-term contracts are in vogue – parties will always be reluctant to agree to a price that would disadvantage them. Even assuming that the parties approach their negotiations with the purest of intentions, they may have a fundamental disagreement over the interpretation and ambit of the price review mechanism or have differing opinions over the effects or relevance of the claimed trigger criteria. They might have conflicting interests that make an amicable settlement difficult or may be facing external pressures imposed by certain stakeholders or constituencies.(28)

In the case of a major shift in global status quo (such as a recession or the discovery of a new energy production source), both contracting parties may be so severely affected that they are unwilling to make any compromise.(29) In such instances, the successful continuation of the commercial relationship requires a binding decision imposed upon the contracting parties. In other words, the disagreement over price evolves into a dispute between the parties and must be addressed by some form of dispute resolution mechanism.

Binding Dispute Settlement Procedure: Objectives

The dispute resolution mechanism in a market reopener clause aims to fulfil the following objectives:

Efficiency

The process must minimize logistical hassles and red-tapism and be as fast and painless as possible. It must also be cost-effective and not impose too much of a financial burden on the parties.

Neutrality

The chosen forum must be neutral. This means that the location, affiliation, or procedure of the forum must not give any disputing party an undue advantage over the other. All entities and individuals that comprise the forum must be independent and impartial. Independence refers to the absence of any relationships or associations that may compel an individual to fall under the sway of a disputing party or an external party that has an interest in the outcome of the dispute. Impartiality, on the other hand, refers to the objectivity of the decision. Any individual presiding over the dispute must not favour or be prejudiced against any of the disputing parties or the specific subject-matter being disputed.(30) It is not enough for an individual to actually be impartial; he or she must also be objectively seen as such through the viewpoint of a reasonable person.(31)

Accuracy

The disputes surrounding price review mechanisms tend to be highly technical in nature. Actual legal issues tend to take a backseat to questions regarding what is commercially reasonable for the industry in light of prevalent geopolitical or economic conditions.(32)

Because this decision will regulate the future commercial relationship between the parties, the decision-maker must exhibit a high degree of understanding over all relevant factors to decide whether trigger conditions have been fulfilled and, if so, what the most sensible response to them is in light of the circumstances, the commodity and industry concerned, and the status of the disputing parties.

Enforceability

An external dispute resolution process is useless if the parties can ignore its outcome with impunity. The outcome of the dispute must be delivered in a method that is final and binding on the parties, leaving little if any wiggle room for a dissatisfied party to avoid complying with its obligations.

Confidentiality

While not an essential criterion, confidentiality may be a desirable trait of a dispute resolution mechanism, as long-term contracts may contain certain proprietary information (eg pertaining to supply chain logistics or management processes) or parties may otherwise want to keep the details of their transactions secret from relevant competitors.

III. AVAILABLE OPTIONS FOR BINDING DISPUTE RESOLUTION

Keeping in mind the essential requirements for an effective dispute resolution mechanism, drafters of long-term contracts are typically left with three potential avenues:

Expert Determination

The disputing parties appoint a neutral expert to make a determination on any matter of fact, valuation, or law submitted to the expert. In other words, it is ‘an inquiry that presents a question to be answered on the basis of individual experience, expert knowledge, and personal inquiry and investigation.’(33)

In a manner of speaking, an expert is not exactly responsible for ‘resolving’ a dispute. Rather, ‘he fills in a space in the contract. He may determine a fact or give a binding opinion with respect to a matter in which he is acknowledged to be an expert.’(34)

An appointed expert does not have any mandatory external rules or due process requirements to guide him in his decision (with the exception of general criminal or civil laws, such as the duty to not accept bribes), and is under no legal obligation to give the disputing parties an opportunity to present their case. (35) Similarly, the expert is not accorded certain privileges that are granted to judges or arbitrators (such as immunity from suit for negligence).

An expert decision can thus be considered a contractual mechanism that adds or revises a clause within contract, rather than an externally-imposed jurisdictional verdict. It can therefore be difficult to enforce an expert determination, as most laws around the world do not contain an efficient framework for this purpose, nor is there any international agreement streamlining the enforcement of expert determinations.

Litigation

Going to the courts is the default option in case a contractual dispute arises, and several price review disputes have been litigated across the world.(36) Traditional courts may possibly help alleviate some of the financial burden of the disputing parties, as the entire process is subsidized by the state.(37)

However, relying on the courts is fraught with several difficulties which makes the procedure an unattractive option. For instance, most jurisdictions may require the proceedings to take place in open court, with all relevant evidence and facts rendered publicly accessible. Developed judicial systems also tend to have at least one (though usually more) levels of appeal, compromising the finality of a dispute and allowing dissatisfied disputing parties to drag the case out for years.

This feature also tends to quickly dissipate any likely savings incurred by opting for a state-subsidized forum. Further, the parties do not have complete control over the procedure and in some jurisdictions may not get the opportunity to insist on a more appropriate, streamlined approach to adjudicating their dispute (eg, dispensing with hearings and obtaining a judgment solely on the basis of written submissions).

Parties usually have no control over who is appointed as their judge in the dispute. Similarly, judges tend to have been primarily working in the legal field for decades rather than being industry experts. In some jurisdictions, contract disputes may also allow the inclusion of a jury of laymen. (38) This all may potentially affect the substantive accuracy of the judgement or at the very least make the decision seem less credible in the eyes of the disputing parties.

The use of litigation becomes a particularly contentious affair in international contracts where the parties are situated in different countries. A party may be unwilling to litigate the dispute in the courts of the counterparty’s country, as it may not be perceived as a neutral forum. For instance, a party may have reservations about the impartiality of the judges or may be unfamiliar with the court procedures adopted.(39)

Most importantly, enforcing a court decision against a foreign party may be very difficult due to the lack of an internationally cohesive framework for the recognition of foreign court judgments. There are some multilateral agreements that attempt to legitimize foreign court judgments passed in signatory states as automatically enforceable (or at the very least with an expedited enforcement mechanism). Examples of such agreements include the Lugano Convention(40) and the Riyadh Convention.(41)

However, such multilateral treaties have failed to attract a significant number of signatories. Several countries enter into bilateral treaties for mutual recognition and enforcement of court judgments, but such bilateral agreements are not consistently widespread, and depend on the relations between the states, their domestic procedures and the similarities between their legal traditions.(42)

Most notably, a major economy like the USA has not entered into bilateral treaties with any other legal jurisdiction.(43) This leaves foreign court judgments to be enforced by a disparate patchwork of systems and approaches, making the entire ordeal unpredictable.(44)

Arbitration

Arbitration involves the adjudication of the dispute by the use of private judging. In other words, arbitration is ‘a process by which parties consensually submit a dispute to a non-governmental decision-maker, selected by or for the parties, to render a binding decision resolving a dispute in accordance with neutral, adjudicatory procedures affording each party an opportunity to present its case.’(45)

Arbitration has emerged as the preferred means for settling price review disputes arising out of long-term contracts, particularly where large amounts of money are involved. There are several reasons behind the success of arbitration for such disputes. Because party autonomy is the cornerstone of arbitration,(46) the parties can tailor the procedure to their liking (subject to minimal mandatory legal requirements to ensure that basic norms of due process are followed).(47)

They can opt to do away with specific mechanisms such as witness cross-examinations or oral hearings in order to make the process more efficient and comfortable for everyone involved. They can even mutually agree on their arbitrators, allowing them to have more trust in the decision and possibly ensuring a substantively more accurate verdict.

“Confidentiality is a hallmark of arbitration”(48), and international parties can appoint neutral arbitrators and seat their proceedings in a neutral legal jurisdiction, thus minimizing any potential wildcards of forum bias.

The biggest reason behind the success of arbitration, however, lies in its enforceability. Unlike expert determination, which is purely contractual in nature, international arbitration is both contractual as well as jurisdictional in nature. This means that an arbitrator verdict may be interpreted as an externally binding decision over the dispute.(49)

Unlike court judgments, for which the international legal framework remains underdeveloped, international arbitration awards are governed by the most successful UN treaty of all time – The New York Convention, 1958. (50) The Convention lays down a harmonized framework for the enforcement of international arbitral awards(51), prescribing the maximum available grounds on which a country may choose to refuse enforcement of an award. The Convention is adhered to by 159 state parties(52) and is arguably responsible for 90% of arbitration awards enforced internationally.(53)

Unfortunately, despite arbitration being the hands-down favourite adjudicatory process for resolving price review disputes – particularly in international contracts – the process has attracted its own share of growing vocal detractors questioning its appropriateness for such disputes.

IV. EVALUATING ARBITRATION AS A PROCESS TO SETTLE PRICE REVIEW DISPUTES

Commentators and practitioners have noted certain disadvantages manifest in the use of arbitration to settle price review disputes. The gist of this criticism centres around the intended role of arbitrators. Despite conventional wisdom dictating that arbitrators are more commercially-minded than judges, arbitration is ultimately meant as a process to resolve legal disputes.

In other words, it is meant as a means to determine what the parties’ rights and obligations are at the time the dispute has been initiated. This is why arbitrations in general (whether contractual or otherwise) involve a backward-looking process, wherein the tribunal inspects the facts and events leading up to the proceedings in front of it and awards damages or other remedies to the claimant in case a breach of pre-existing legal obligations has occurred.

The tribunal does not really concern itself with events that will happen subsequent to the issuance of the award.(54) Indeed, one Austrian Supreme Court judgment from 1985 ruled that the adaptation of a contract by arbitrators would constitute an expert determination rather than an arbitration proceeding. (55)

Price review arbitrations, on the other hand, are quite a different breed. Firstly, the amount of ‘legal’ issues at play are virtually non-existent. No party can truly be said to be ‘at fault’(56) and the arguments rarely hinge around rights being infringed or promises being broken. Furthermore, the tribunal is required to ‘exercise both backward-looking and forward-looking judgment.’ (57)

The arbitrators are required to peruse the facts and events leading up to the review date (While excluding those events and facts that occur after the review date and during the negotiations/proceedings) in order to ascertain whether a valid triggering event has occurred. Once a triggering event has been established, the arbitrators must ascertain to what extent it has destabilized the commercial balance between the parties. All of this requires backward-looking judgement.

However, after all of the above is done, the tribunal must start arriving at a new commercial equilibrium to govern the parties’ long-term relationship. The arbitrators must impose a price in accordance with contractually-specified criteria - one that will be fair and will best serve the mutual interests of the parties. In a sense, the arbitrators become more like business advisors rather than adjudicators.

The fact that they are not officially mediators or advocates for the parties and are thus not privy to the parties’ true motivations or concerns (58) makes the task all the more difficult for them. The contractually-specified criteria for determining the new price cannot exhaustively determine the new price and there is a lot of wiggle room left for the tribunal’s judgement to fill out. The new price must thus be as objectively reasonable as possible.

However, the entire notion of what is reasonable is something that is heavily shaped by an individual’s background and circumstances. In order to determine whether a specific pricing solution makes commercial sense, it helps to have a diverse tribunal that can impartially evaluate factors such as different business sensibilities, risk appetites, and negotiation practices (among others). It is a well-documented observation that members of different professions tend to think differently due to their specific training and educational background. They may approach an issue with different assumptions, incorporate different methods of analyzing facts, prioritize different variables and may even have different standards of what exactly is ‘fair.’(59)

Since a price review determination is ultimately aimed towards a solution that is commercially sound (as opposed to merely legally sound), a diverse jury is more comfortable with assessing commercial reasonability from different perspectives. Economists or commodity traders may differ from lawyers when it comes to prioritizing or understanding subjective values due to their professional training. Similarly, accountants might just have different risk appetites that would shape their perception of a sensible solution.

All of these variegated perspectives come together to ensure that the ultimate verdict is as objective as possible, rather than one tainted by groupthink. An individual’s values and decision-making processes are not just affected by their professional background, but also other variables such as their gender, ethnicity, place of residence, age and social class. Indeed, this is why experienced arbitration practitioners and institutions are currently stressing the importance of improving the diversity of contemporary international tribunals. (60)

However, there is a limit to how representative or diverse conventional arbitration tribunals can get. Tribunals usually consist of either one arbitrator (for low value disputes) and three arbitrators (for high value, complex disputes). On rare occasions there may even be five- (61) or seven- or nine-member (62) tribunals. While there is no theoretical limit on the number of arbitrators that may be appointed, (63) a tribunal manned by more than three arbitrators tends to get logistically unwieldy and prohibitively expensive. It appears then that in most cases the “objectively reasonable commercial solution” to price review disputes is really just the consensus of at least two out of three handpicked individuals – most of whom tend to come from the relatively insular international arbitration industry. (64)

The arbitration process also has certain other associated shortcomings. For instance, despite celebratory claims made by arbitration proponents regarding how arbitration is faster and cheaper than litigation, empirical evidence suggests that the process does not necessarily deliver as much as hoped on those two fronts. (65) Indeed, in cases where hundreds of millions or billions of dollars are at stake, proceedings may stretch on for years and cost well into the tens of millions of dollars. Admittedly, most of the costs are associated with legal representation rather than arbitrator fees or institutional expenses, (66) but time and costs can unnecessarily pile up due to logistical issues such as the coordination of arbitrator schedules. While party autonomy in theory is supreme and the parties can mutually agree to make the proceedings as efficient as possible, in practice this is very rare as the parties tend to be focused more on securing their own interests rather than cooperating with each other. In such a scenario, control of the procedure defaults to the arbitrator and arbitral institution (where applicable), and both tend to play it safe with their procedural decisions because of due process paranoia (67) - thus rendering the proceedings slower than initially expected.

The sluggish pace of arbitrations can also affect arbitrator decision-making and the substantive accuracy of the award itself. This is because arbitrators are expected adjudicate the issues based on the facts and circumstances that existed at the time the dispute was initiated (the very moment one party approached the other with a view to renegotiate the contract). The award is not supposed to be contingent upon any facts or events that emerged after negotiations broke down or while the arbitral proceedings were under way. However, in practice it is extremely difficult for the tribunal to ignore relevant facts that happened after the stipulated review date, especially since they are under pressure to arrive at a commercially reasonable decision. (68)

Enforcing a judgment may increase these headaches in case the losing party refuses to voluntarily comply with the arbitral award, as then the winning party will have to approach courts with jurisdiction over the recalcitrant party to enforce the award.

Despite these glaring shortcomings, international arbitration is better placed to settle unsalvageable price review disagreements than any other existing dispute resolution process. Indeed, the popular adage for democracy seems apt here: Conventional arbitration is the worst process for settling a stalled voluntary price review dispute, except for all other processes that have been tried.

However, what if there was a process that has not been tried before? One that contains or even improves upon several of the advantages of arbitration while at the same time lacking some of its weaknesses?

V. KLEROS: A BETTER ALTERNATIVE?

The use of blockchain technology would streamline the price review process in several ways. Firstly, it is likely that some disagreements would be nipped in the bud, as smart contracts could be programmed to adjust the payable price in accordance with the relevant indices automatically without any human input. This would allow a more realistic price flow from the buyer to the seller.

For instance, where gas prices are benchmarked in accordance with the price trading at a nearby gas trading hub, the contract price or supply quantity could be automatically adjusted daily rather than monthly in order to ensure the most realistic value. Of course, just like regular contracts, a smart contract cannot be programmed to anticipate infinite possibilities, and a price review request would arise sooner rather than later. This is where Kleros’ oracle use case comes in handy, as it is ‘capable of providing a fine-grained estimate of a price of a generic asset, as for use in a financial contract, in a satisfying, fully decentralized way.’ (69/70)

Kleros’ method of blockchain-based crowdsourced arbitration has the potential to emerge as the most appropriate forum to settle price review disputes arising out of long-term contracts. This may be understood by evaluating how well the system fulfils the desired requirements of a dispute resolution mechanism highlighted in Part II:

Efficiency

The use of Kleros would substantially reduce the expenses involved with initiating and administering arbitration proceedings. While it is unlikely that the fees charged by legal counsel or expert witnesses would markedly decrease, the blockchain ecosystem would eliminate several associated expenses such as travel, accommodation and the hire of hearing facilities. The process would be speedy as well, as jurors would be able to vote on the issues as and when it is convenient to do so. Even more time and money can be saved if the entire transactional process was conducted on the blockchain ecosystem from the very get-go, as procedures such as document verification and evidence authentication would take place instantaneously. (71)

Kleros offers many of the same advantages of party autonomy that conventional arbitration does. The contracting parties can mutually agree upon the procedure by which their dispute will be judged. Indeed, there is no theoretical bar to having oral hearings or presentations if the parties or jurors so desire. They can determine the type or form of evidence that will be presented or how many appeals there will be. And much like how parties select arbitration rules in conventional proceedings, parties to a Kleros dispute can even opt-in to the rules of a specific sub-court – quite feasibly a sub-court that has been created specially for energy industry disputes.

Neutrality

Kleros’ defining tagline is that it delivers ‘decentralized justice.’(72) What this implies is that the system by design is meant to be a neutral forum that cannot be influenced by a powerful party or contain any inherent geopolitical biases. In fact, Kleros takes the principle of decentralization to its logical conclusion: The entire project is open source and available for inspection, and the governance is democratically led by a social cooperative that consists of all relevant stakeholders who choose to opt-in. (73) This makes it impossible for the developers to make any alterations that would hurt the neutrality or reliability of the Kleros Court. The biggest objections that users of price reviews may have is towards the independence and impartiality of the jury.

In traditional arbitration, the independence and impartiality of arbitrators is a big deal, and a violation of these principles may lead to the removal of the arbitrator and/or a successful challenge or refusal of enforcement of the award. Regular users of arbitration utilize lots of time and resources in vetting arbitrators. A potential arbitrator’s public statements are combed through to ensure that he has not criticized any party to the dispute or taken a legal stance on it before even being appointed. (74)

Arbitrators are subjected to an ever-increasing list of disclosure requirements where they are expected to reveal any relationship or links they may have with parties, counsel, witnesses, third-party funders and others involved with the arbitration. (75) Arbitrators must not have any ex parte contact with the parties. Some arbitration rules even discourage arbitrators from sharing the same nationality as any party to the dispute. (76)

Indeed, it is possible that an arbitrator will be challenged if her mutual fund portfolio contains shares of a disputing party even if she had no knowledge of the fund manager’s individual stock picks. It can thus be deduced that traditional arbitration is built upon trust. Arbitrators are held to an impeccable standard of trustworthiness and must be objectively viewed as such even by disinterested third parties.

On the other hand, Kleros eliminates the concept of ‘trust’ entirely. The jurors are anonymous, so the entire point of party selection is rendered moot. Jurors instead stake their pinakion (PNK) into the dispute and are drawn randomly from the pool, with their probability of selection directly contingent upon how much they stake. Some critics may point out that this feature would kill any desire for parties to refer their disputes to the Kleros forum, as one of the most popular motivations for opting for arbitration instead of litigation is the opportunity for parties to choose their judges. (77) Others still may point out that such a structure will not screen jurors for bias at all, and theoretically even parties could become a judge in their own case.

The first concern is valid and cannot really be denied, although it is posited here that parties will not much decry their inability to choose jurors in light of the other benefits provided by the Kleros system. (78) The second objection, on the other hand, is suitably addressed through cryptoeconomics – in particular, the Schelling Point principle. (79)

An amount of the juror’s staked PNK are forfeit if she votes inconsistently with the majority of jurors and distributed to the consistent jurors. While all jurors earn fees in ether (ETH) for their services, (80) staking PNK is necessary for them to actually have the opportunity arbitrate the dispute (Not to mention that PNK have a monetary value of their own). Note that the individual juror does not normally know who her peers are or their affiliations (although different sub-courts may opt for different policies); all she knows is that those who are coherent with the majority of jurors are rewarded and those who are incoherent will be penalized.

This layer of anonymity nullifies any chance of the jurors collaborating with each other to come to a verdict, which means that the default assumption is that each juror will expect her counterparts to decide ‘truthfully’. (81) Additionally, the Kleros system is designed to support appellate mechanisms, where a dissatisfied party can appeal the verdict of a dispute to a larger jury. If the appellate jury overturns the award, then the inconsistent appellate jurors as well as the jurors which made the initial majority both lose their PNK to their counterparts.

This possibility of an appeal reinforces the incentive of a juror to vote ‘truthfully.’ It is thus unimportant that an openly biased juror may be drawn to judge a dispute. The entire system is deliberately designed to financially penalize jurors who try to manipulate the outcome of the dispute. A measure of last resort would involve the hard fork of the Kleros ecosystem in order to reverse a particularly repugnant decision – something that would require community consensus.

But what about bribery? Isn’t the crypto world a hive of money-laundering and drug deals? It would be naïve to insist that litigation or arbitration verdicts are never tainted by bribery. Quite the contrary, actually.(82) Indeed, voter anonymity, appellate mechanisms and the Schelling Point principle makes it more difficult for parties to bribe Kleros juries than they could under other dispute resolution processes. (83)

Kleros’ use of the PNK also deserves a mention for its contributions towards maintaining the integrity of the process. A native token makes a 51% attack difficult because of the native token’s relative scarcity and price volatility as opposed to ETH, thus making the consolidation of PNK into one entity’s possession difficult. Further, a native token renders Kleros forkable, which could be used as an ‘ultimate appeal mechanism’ in case the market decides that the integrity of juries has been compromised. (84)

Accuracy

Even if 100% of Kleros jurors are impartial and independent, this alone would not be enough to alleviate apprehensions about relying on crowdsourcing for highly technical questions. As mentioned earlier, market reopener clauses rarely involve questions of rights and liabilities, and there isn’t exactly a party who has behaved improperly. The dispute essentially centres around the creation of a new deal that would best serve the mutual interests of the parties. It is thus important for jurors to be able to put themselves in the shoes of the parties and command a high degree of understanding over the relevant subject matter of the dispute and the prevailing market conditions.

Failing the ability of parties to directly choose their jurors, they must resort to laying down certain mandatory juror qualification criteria in their arbitration agreement or relying on subcourt policies. However, this is not necessarily a bad thing, considering the forward-looking nature of price review arbitrations. The majority of arbitrators in traditional arbitral proceedings happen to be legal professionals. A tribunal of three arbitrators might sometimes include a technical expert (though he will tend to be someone with some legal training or has spent a lot of time around lawyers).

While such a situation may be acceptable for legal disputes, it is counter-productive for disputes which require commercial solutions. The logistical hurdles, scheduling conflicts and expenses associated with organizing larger, more diverse tribunals will be largely absent from the Kleros process, as adjudicating a dispute on a blockchain-based online platform allows for more operational flexibility than offline hearings. Parties are no longer confined to three- or five-member tribunals in case they want a more objectively sound resolution of their dispute. Now there can be dozens of jurors, each with a different level of expertise and knowledge all coming together to settle upon a focal point.

For instance, assume a dispute arising out of an electricity wholesale contract (85) where the buyer wants to negotiate a lower price because the end-user market that the buyer supplies is unable to afford the current rates. A price review dispute can be referred to Kleros using its Oracle use case, where respondents will submit value ranges to determine whether the price must change and, if so, by how much. The focal point will be an overlap between a diverse set of people: people who hold shares in either or both contracting parties, accountants, economists, municipal civil servants, residents of the end-user market, environmentalists, etc.

Even if the parties or the sub-court opted to restrict juror participation - perhaps by stipulating that only those who have a law, economics or accounting degree are eligible to be respondents – the jury would still be immensely more diverse than a traditional tribunal. (86)

The overlapping price ranges will converge upon a price point that reflects the perspectives and understanding of a large swathe of very different people; therefore having a better claim to be considered ‘objectively reasonable’ than a single person’s assessment or an agreement between at least two out of three arbitrators.

Perhaps the price so reached won’t truly fulfil either or both parties’ actual commercial interests – but it would likely come closer than any other method the parties have at their disposal precisely because it would be more objective. (87) The ability to host larger and professionally diverse (yet still competent) juries thus gives Kleros the potential to outperform conventional arbitration as far as substantive justice goes.

Enforceability

Kleros’ Escrow use case could be utilized to render the jury award automatically enforceable. The jury’s decision can send automated orders to smart contracts that a) Are connected to the parties’ bank accounts and remit funds from the buyer to the seller as per the stipulated payment plan, and/or b) in instances where there is an installed supply network (such as electricity grids or gas pipelines), regulates the supply amount. The smart contracts would execute commands as per the jury’s final verdict.

For instance, where a jury has decided that there are mitigating financial circumstances in the buyer’s end-user market, it can render a verdict that mandates a lower price payable to the seller. Once the verdict is final (ie the seller accepts the verdict, the time for appeal has passed, or the appeals have been exhausted), the smart contract will kick in and start deducting a lower amount of money from the buyer’s funds until the next price review. (88)

In this sense, Kleros is automatically enforceable because the parties do not have to take any additional steps in order to ensure mutual compliance with the verdict. However, it must be borne in mind that a Kleros verdict is not yet legally enforceable.

Legal enforceability of an award means that courts of law will consider it a valid judgment that establishes the rights and obligations of the disputing parties. The courts will then pass suitable orders for the award’s execution if necessary. This principle generally comes into play when a party disagrees with the decision and refuses to comply voluntarily.

To illustrate, an arbitrator has no state agencies at his disposal and cannot directly order attachment of assets or civil imprisonment in case a respondent refuses to pay damages owed to the claimant. To ensure that the order is complied with, the claimant must approach courts with jurisdiction over the respondent and obtain an enforcement order. The court will execute the arbitrator’s award provided that the award complies with the formal requirements (89) and the resisting party is unable to demonstrate any reasons that enforcement should be refused. (90)

However, legal enforceability is not just relevant to ensure that the resisting party complies with the terms of the award. In a blockchain-based price review dispute such an action will generally be unnecessary as the smart contract will automatically make the necessary alterations to the flow of funds. But a concept closely intertwined with legal enforceability – indeed, a necessary subset as far as jurisdictional awards go - is that of legal recognition. (91)

Legal enforceability is a sword while legal recognition is a shield. (92) The former ensures that courts will take active steps to ensure that the will of an award is carried out whereas the latter guarantees that the courts will consider the award as one that has been passed down by a valid adjudicatory authority with jurisdiction, therefore refusing to question, reopen or alter the substance of the verdict. Legal recognition ensures that courts will uphold the principle of res judicata – barring parties from relitigating any issues that have been settled between them by a court of jurisdiction.

This is how a conventional arbitration award differs from an expert determination. The transnational legal framework bestowed by the New York Convention and domestic laws give widespread legal recognition to arbitral awards. Most courts that respect the rule of law will refuse to allow parties to relitigate any issues that have been duly considered by an arbitral tribunal.

Expert determinations, on the other hand, offer no such robust transnational framework for recognition. They are instead governed by principles of contract law. Individual jurisdictions will differ greatly in the respect they accord to the process. Some courts may decide to give great reverence to the findings of the expert and refuse to alter it except in the most extreme circumstances while others may choose to merely treat the findings of the expert as it would any other argument put forth by a disputing party. Regardless of the differing approaches and attitudes, one trend common among all courts is that they will view the expert determination as a contractual mechanism.

The expert is working in a purely professional capacity to represent the ostensible will of the parties and interpret what the contract says instead of finally determining the rights and obligations of the parties. The expert determination does not preclude courts from determining the very same issues and thus has no jurisdictional impact. The expert can be held liable for simple professional negligence unlike arbitrators (who tend to have varying degrees of immunity) and, unlike arbitral awards, the determination itself can be set aside or altered on the merits. (93)

Kleros will most certainly not qualify as an arbitral award under the current legal framework and instead will be considered a contractual mechanism for dispute settlement. Considering that contemporary courts are generally not very friendly towards anonymity or potential conflicts of interest and are bound to be unconvinced by any talk about ‘schelling points’, it is most likely that Kleros jury verdicts will be granted even less deference by courts than expert determinations.

What this means is that the losing party can freely approach any court with jurisdiction over the counterparty and subject-matter and demand a re-litigation of the dispute, claiming that the contractual dispute settlement mechanism that the parties had agreed upon (Kleros) failed to achieve a just solution.

In the best case scenario, the court will rule the same way as the Kleros jury – wasting a substantial portion of the parties precious time and resources (not to mention likely compromising the confidentiality of the contract). (94)

In the worst case scenario, the court will rule on the dispute an entirely different way, thus destroying the predictability and certainty that parties desire when agreeing on a dispute settlement mechanism. Turning Kleros into a legitimate dispute resolution internationally is the first and most crucial step required before it can be adopted as a mechanism for disputes that involve very large claim sizes.

Without any robust transnational framework that legitimizes Kleros, this discussion will remain of purely academic value. However, solving this problem merits a separate discussion of its own.

Confidentiality

Considering the immense importance placed upon confidentiality by parties to long-term energy supply contracts, (95) Kleros will never be adopted as a solution if it does not address this particular concern – even if the system otherwise saves the parties millions of dollars and cuts the lifetime of the dispute by several months.

While the current iteration of Kleros does not offer such features, this is primarily because the project is still in its early days and still smoothing out its kinks with the help of early adopters. There is nothing stopping the software from being upgraded and allowing additional features that will facilitate a comprehensive framework of confidentiality.

Methods such as asymmetric encryption could be used to ensure that only the jurors have access to secured confidential information. Sub-courts could draft policies that require the verification of juror identities for the purpose of legally binding them to non-disclosure agreements. If deemed necessary, secret voting could be implemented to ensure that jurors do not try to ‘game the system’ and vote on the basis of the evidence and arguments the parties have presented rather than on the basis of how their co-jurors are voting.

It appears, then, that as a dispute resolution process, Kleros is well-placed to replace conventional methods when it comes to disputes arising out of market reopener clauses. However, certain changes in prevalent laws, attitudes and expectations are required before the proposal can gain any serious traction.

IV. LOOKING FORWARD

It is no great feat to sit in an armchair and make recommendations for change or improvement. The real challenge lies with making ideas practicable and implementing them. Kleros undoubtedly has the potential to revolutionize dispute resolution across the spectrum of human endeavours. However, in order for it to acquire legitimacy and widespread adoption, several hurdles – technical, legal, and psychological - will have to be removed.

On the technical side, several improvements and advances within blockchain technology will need to be made before DApps and decentralized smart contracts can be used widely. The underlying Ethereum blockchain can only process 15 transactions per second. To put things in perspective, Visa is allegedly capable of processing 24,000 transactions per second,(96) and, according to Vitalik Buterin, Ethereum will require a processing speed of 100,000 transaction per second in order to be a viable platform.(97) The Ethereum Project is actively moving towards this direction, with the Serenity upgrade – which will purportedly make Ethereum 1000x more scalable – expected to release in 2021.

Navigating the legal landscape will be a far more challenging task than sorting out all the technological barriers. The blockchain realm exists in a convoluted legal purgatory, with no transparency or consistency regarding its status. Governments around the world appear to be simultaneously enamoured and repulsed by blockchain technology.

For example, the Indian Central Bank has prohibited all financial institutions from dealing in cryptocurrencies while the Prime Minister has hailed the potential revolutionary nature of blockchain. (98) China’s internet regulator approved 197 firms to commence blockchain-based services in the country while the government wants to ban cryptocurrency mining, citing energy wastage concerns. (99) The adoption of Blockchain applications will require the amendment or removal of outdated laws in a variety of areas, including land records management, evidence production in courts, tax law, etc.

Dispute Resolution is one such area that will require radical legal changes before services such as Kleros can gain legitimacy. As mentioned in the previous section, Kleros will likely not be considered a legally enforceable or valid dispute resolution process under the present framework. This is because the system violates some core tenets of the principles of due process as widely understood today. Namely, it is a private dispute resolution process that does not give parties the opportunity to choose their judges – an issue that has led to courts invalidating arbitration awards. (100)

Further the juror selection process enables vested interests (including the parties themselves) to be drawn as jurors. In fact, there is also a possibility that someone with enough PNK to stake can be drawn as a juror in a dispute more than once. A major cultural shift in jurisprudential discourse is required before courts and legislatures start taking crypto-economic concepts seriously. (101)

The ideal way to foster global adoption of Kleros would be to retrace the steps that conventional arbitration took, with the universal proliferation of a model law (102) or the adoption of a multilateral treaty to harmonize the enforceability and recognition of Kleros awards.

However, this is a gargantuan task. Coming up with a new multilateral treaty or amending the New York Convention is no small feat and will require global consensus among all signatory states. More importantly, before one can start approaching courts and legislators to completely overhaul the dispute resolution legal framework, it is imperative to garner unwavering support from the intended consumers of the service.

While lower costs and speedier resolution of disputes will certainly stimulate interest in low value and simplistic disputes (particularly those that would otherwise not end up in court), end-users may initially be less willing to crowdsource disputes that involve complicated questions of law and fact or involve large sums of money. This is particularly the case with parties that typically enter into lucrative long-term contracts: multinational corporate giants under constant public scrutiny and integral government agencies with several stakeholders to answer to – entities that may not exactly be comfortable staking obscene amounts of money to experiment with an untested dispute resolution process where they do not even know who their judges are.

All arguments based on crypto-economics or game theory may fail to dissipate the technological suspicion of jaded executives and the equally jaded transactional attorneys that advise them. These barriers to greater adoption are mainly psychological, and have been systematically ingrained over many years.

Overcoming them will require patience, education and the intelligent promotion of blockchain-based services. Admittedly, we might have to wait a while before we see parties referring billion-dollar, bet-the-company disputes to Kleros (particularly those that arise in the off-chain world). Does that fact make this article a mere futuristic opinion piece with an interesting idea but no immediately practicable value? Not necessarily.

This article focused largely on long-term contracts in primary resource industries because those are where the lack of a proper dispute settlement mechanism has been felt most significantly. For example, price review arbitrations in the LNG industry are, ‘as a collection of cases, the highest-value commercial disputes in the world today. The amounts at stake begin in the hundreds of millions of dollars and often climb into the billions.’ (103)

A significant chunk of these billions being staked happens to be public money, and the knock-on effects of such arbitrations affect more stakeholders than just the two corporate entities involved. It is imperative that such disputes are settled as efficiently and fairly as possible, more so than most other kinds of disputes.

However, price review mechanisms are also commonly found in lower-value, comparatively mundane long-term contracts, such as land and property leases (104) and long-term maintenance and repair contracts. (105)

Regardless of the values being staked, all of these contracts ultimately involve arriving at commercially sound decisions that will govern the parties’ future relationships. Perhaps these ‘low-hanging fruit’ (comparatively speaking) are appropriate candidates to test out Kleros’ Oracle and Escrow use cases in reworking parties’ commercial transactions before the platform can set its sights on the bullseye of long-term energy supply contracts.

Footnotes

- Michael D Bayles, ‘Introduction: The Purposes of Contract Law’ (1983) 17(4) Valparaiso University Law Review 613, 616

- Ren Orans, CK Woo and William Clayton, ‘Benchmarking the Price Reasonableness of a Long-Term Electricity Contract’ (2004) 25 Energy Law Journal 357

- Chauncey SR Curtz, ‘Market Price Reopeners in Long-Term Coal Supply Contracts: The Lessons of Recent Litigation and Arbitration’ (1994) EMLF White Paper

- David Mildon, ‘Successive disputes under long term contracts: when can issue preclusion arise?’ (Essex Court Chambers) <https://essexcourt.com/publication/successive-disputes-under-long-term-contracts-when-can-issue-preclusion-arise/>

- Long-term contracts arising out of such primary resource industries will be referred as ‘energy supply contracts’ throughout this paper.

- Justin Fox, ‘Stop Calling Shell an Oil Company’ (Bloomberg, 9 Apr 15) <https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2015-04-08/maybe-it-s-time-to-stop-calling-shell-an-oil-company>

- See eg Nicholas Moussas, ‘Take-or-pay clauses in the natural gas sales contracts and potential claims against buyers’ (Lexology, 17 Oct 16) <https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=57bbd39f-9109-4d40-8f4a-16a2c07d1279> (‘The take-or-pay clause is activated when the buyer does not offtake the entire quantity of the natural gas he had ordered. In many cases, the latter is required to pay the purchase price for a minimum quantity of natural gas (make up quantity), defined in advance even if it has not purchased said quantity within the respective year. Usually, the buyer may offtake the make-up quantity in future contractual years either by paying a special price fixed anew or without any obligation to pay for the second time.’)

- ‘Vattenfall Secures New Nuclear Fuel Supply’ (Global Energy World, 14 Dec 16) <http://www.globalenergyworld.com/news/traditional-energy/2016/12/14/vattenfall-secures-new-nuclear-fuel-supply>

- See eg, Gas Supply Agreement between Corning and KeySpan (SEC filings) <https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/24751/000002475105000040/cng8k10-2v2.htm> ; Coal Supply Agreement between Wabash River Energy and Midwest Mining Company (SEC Filings) <https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1401698/000119312507138594/dex1023.htm>

- See Bruce B Henning ‘Long-term Contracting for Natural Gas: Examination of the Issues that Affect the Potential for the Increased Use of Contracting to Stabilize Consumer Prices’ (Bipartisan Policy, 09 Jun 11) <https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/default/files/Henning%20Long-Term%20Contracting.pdf> 1 (‘Long-term contracts can serve as a “hedge” on price movements for consumers’)

- Meldina Kokorovic Jukan, Admir Jukan and Amir Tokić, ‘Identification and Assessment of Key Risks and Power Quality Issues in Liberalized Electricity Markets in Europe‘ (2011) 11(3) International Journal of Engineering & Technology 22, 23 ; Ryan Wiser and others, ‘Comparing the risk profiles of renewable and natural gas-fired electricity contracts’ (2004) 8(4) Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 335, 338-339

- Note: This is an indicative list.

- In some cases, this may even be politically motivated. See generally Michael Parkin, ‘The Politics of Inflation’ (1975) 10(2) Government and Opposition 189

- See eg Chris Ross, ‘LNG Projects Have Stalled. A New Business Model Could Help’ (Forbes, 14 May 18) <https://www.forbes.com/sites/uhenergy/2018/05/14/lng-projects-have-stalled-a-new-business-model-could-help/#58278ffb4f14>

- Justin W Ross, ‘Reopening Pandora’s Box: Market Price Reopeners in Volatile and Uncertain Times’ (2013) 34 (13) Energy and Mineral Law Institute 553, 556

- See generally Piero Bernardini, 'Stabilization and adaptation in oil and gas investments' (2008) The Journal of World Energy Law & Business 98

- Ross (n15) 556

- A gas trading hub is essentially a point where gas sellers and buyers can easily come together to transfer possession of natural gas. Situated at the heart of the regional gas supply infrastructure, such as LNG terminals, pipeline networks, and shipping ports, it functions as a central pricing point for gas trading in the network, and generally gives rise to the development of a sophisticated derivatives market (in addition to the underlying commodity market). A gas hub can only be created in areas that have a developed pipeline network and ample storage facilities in order to enable vast quantities of gas to be moved around at short notice. Successful gas trading hubs will typically have access to several competing sources of gas supply (ie domestic production, pipeline supply and overseas shipments) as well as a diverse end-user base (ie both domestic and industrial consumers) in order to ensure a balanced, competitive marketplace. A gas trading hub also requires tremendous political will to deregulate the gas market and allow prices to develop organically. Examples of gas trading hubs include the Henry Hub in Louisiana (which connects pipeline networks across continental United States) or the TTF in Netherlands and the BNP in UK (both of which function as virtual trading points for the European gas markets).

- Holly Stebbing and Matthew Plaistowe, ‘The transformation of the global gas industry’ in Norton Rose Fulbright, International Arbitration Report (Issue 11, Oct 2018) <https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/-/media/files/nrf/nrfweb/imported/international-arbitration-review---issue-11.pdf?la=en&revision=f23f1aee-4947-4743-86a2-b9b74ed6e191> 20,22 (‘In Europe, at least, some now argue that where the pricing formulae is linked to a European gas hub, price review clauses are unnecessary as the contract price should always track the market and there is no risk of divergence as there was for oil-linked contracts. If that proves to be correct, price review arbitrations in Europe may die out. However, even where there is hub pricing, there is still the risk that the hub price and the price in the end users’ specific market may diverge (particularly given the destination flexibility offered by LNG where the hub reference could be geographically distant from the buyer’s market) and this may trigger price review disputes.’)

- There may sometimes be good reason to doubt the authenticity of prices listed on gas trading hubs in case the hub is de facto controlled by a single corporate entity or government with a reputation for a lack of transparency and potentially manipulating prices. See, Rudolf ten Hoedt, ‘Singapore’s push to be Asia’s first LNG trading hub & the uncertain future of the Asian gas market’ (Energypost.eu, 28 Oct 14) <https://energypost.eu/singapores-drive-become-asias-first-lng-trading-hub-uncertain-future-asian-gas-market/>

- See eg, Duke Energy Indus. Sales, LLC v. Massey Coal Sales Co., No. 2930772, 2012 WL (S.D.W. Va. July 18, 2012) [3]

- Michelle Cole, ‘Price review clauses in long term energy contracts’ (Lexology, 13 Sep 12) <https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=6f5f65fa-0e23-4917-b56e-0bfd0e22f322>

- John A Trenor, ‘Gas Price Disputes Under Long-Term Gas Sales And Purchase Agreements’ (2017) The Energy Regulation and Markets Review – Edition 6 <https://thelawreviews.co.uk/edition/the-energy-regulation-and-markets-review-edition-6/1144302/gas-price-disputes-under-long-term-gas-sales-and-purchase-agreements> (‘The clause typically specifies a limited number of such joker price revision requests that can be made; for example, two over the lifetime of the contract or one during a specified period and a second during a later period.’)

- Curtz (n3) § 6.03[1][b]

- Gas Natural Aprovisionamientos, SDG, S.A. v. Atlantic LNG Company of Trinidad and Tobago in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (2008) WL 4344525 (S.D.N.Y.)

- See Trenor (n23)

- See eg Louis Chiam and Vishal Ahuja, ‘Long-Term Supply Contracts – Time For Review’ (2006) 25 ARELJ 149, 164 (‘Where changes in circumstances occur, the contract will often require the parties to negotiate changes in good faith. Even if it is not an express requirement of the contract, it may well be that Australian Courts will imply an obligation to perform a commercial contract in good faith where it is not inconsistent with the express terms of the contract. While negotiation in good faith involves an obligation to act reasonably and honestly and not arbitrarily or capriciously, it does not require a party to act contrary to its own legitimate interests.’) See also eg Ross (n15) 562-564 (giving examples of legal disincentives to ensure that parties do not forego their duty to negotiate in good faith).

- For instance, in an election year the government overseeing a large oil and gas producing state-owned-corporation may be unwilling to reduce the corporation’s revenues.

- Indeed, price review disputes in the LNG sector have arisen in ‘waves’ following radical market changes such as the liberalization of European gas markets, the great recession of 2008, the rise of fracking in the USA, or the development of sophisticated trading hubs. See generally Stephen P Anway and George M von Mehren, ‘The Evolution of Natural Gas Price Review Arbitrations’ in J William Rowley (ed), The Guide to Energy Arbitrations (3rd edn, Global Arbitration Review 2019) <https://globalarbitrationreview.com/chapter/1178846/the-evolution-of-natural-gas-price-review-arbitrations>

- Diego M Papayannis, 'Independence, impartiality and neutrality in legal adjudication' (2016) 28 Issues in Contemporary Jurisprudence 33 [5]-[6]

- OHCHR, Human Rights in the Administration of Justice: A Manual on Human Rights for Judges, Prosecutors and Lawyers (UN 2003) 120

- This will be explained further in Part IV

- Cole, (n22)

- RMB Reynolds, ‘Problems With Long Term Contracfs: Alternative Methods Of Resolving Disputes’ (1986) AMPLA Yearbook 451, 459

- Ibid 461

- See eg Diversified Energy, Inc. v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 223 F.3d 328 (6th Cir. 2000); PSI Energy, Inc. v. Exxon Coal USA, Inc., 831 F. Supp. 1419 (S.D. Ind. 1992); Xstrata Queensland Ltd v Santos Ltd [2005] QSC 323

- While parties may have to pay expenses such as court fees, these are generally nominal.

- See eg U. S. Const. amend. VII (‘In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law’).

- It is possible to insert an exclusive jurisdiction clause that would refer all disputes to the courts of a third country. However, one must also bear in mind that the courts of the third country may not be interested in wasting resources over a dispute that has no material connection with their jurisdiction.

- Convention on Jurisdiction and the Recognition and Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters [2007] OJ L339/3

- Convention on Judicial Cooperation (Arab League) (signed 8th Apr 1983, entered into force 1st Oct 1985) (Riyadh Convention)

- Ralf Michaels, ‘Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments’ in Max Planck Encycopedia of Public International Law (OUP 2009) [13]