Eyal Winter: On Game Theory, Decentralized Justice and Kleros

Eyal Winter: On Decentralized Justice, Dispute Resolution systems and the Future of LegalTech

Kleros' approach to arbitration is based on cryptoeconomics as to produce the right incentives for jurors to arbitrate disputes honestly. Eyal Winter is exploring the opportunities and challenges of applying game theoretical principles into decentralized justice...

Tell us a little bit about your background, how did you get interested in game theory?

I got interested in game theory early in my studies, because Israel is to some extent an empire in game theory. We have a Nobel laureate in game theory, Robert E. Aumann, here at The Federmann Center for the Study of Rationality at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, a few doors away from me.

I studied with him and did my PhD in game theory here at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. When I finished, I went for my postdoc with Alvin Roth, who got the Nobel Prize in 2012. Then I moved for my PostDoc to Germany to study with Reinhard Selten who also got his Nobel prize in 1994 (shared with John Nash). I was surrounded by a lot of Nobel prize laureates who encouraged me to do research in this field.

I was a professor in the Washington University in Saint Louis in the United States for several years, then at Manchester University, then at the European University Institute in Florence, then I came back to Jerusalem and moved around a little bit more. Now I have two positions, one here at the Hebrew University and one in Lancaster University in the UK.

As I started working in game theory, I gradually noticed that to understand how people behave and to utilize game theory to a full extent, you also need to understand economic behavior, which is the borderline between psychology and economics.

So I got into experimental economics and published some works on decision making using experiments and also using game theoretical insights into how people vote, how people make decisions collectively and how committees make decisions. These are the areas I am primarily working in.

Apart from my academic research, I have been engaged with a lot of consulting work, both in governments and with corporations and NGOs. I was leading a group at the Israeli government which did something similar to the group in the UK called the Behavioral Insight Team, that tried to bring economic behavioral insight into policy making to improve regulation in a variety of issues in the way government offices are making decisions.

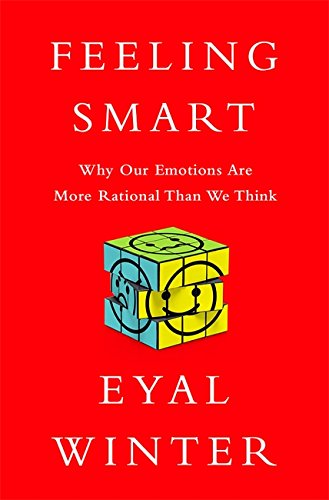

In recent years, I also tried to make my research accessible to people outside of academia. For example, through my book “Feeling Smart - Why Our Emotions Are More Rational Than We Think”, that I first wrote in English and was then translated into seven languages. It’s a book that tries to explain how we make decisions utilizing both rationality and emotions.

How did you start researching the connection between game theory and legal systems?

Legal systems, to some extent, can be portrayed as a game. I have several joint works with people who work in law in Israel on theoretical works on how to design constitutions: how to design a legal system that is economically optimal? How do you draft a bill that will have the maximal ability to deter at minimal cost? How do you allocate cost in tort law?

These issues require game theoretical insight. These collaborations are with legal people that need my expertise in game theory and I enjoy doing it.

On the other hand, my other PhD supervisor, Bezalel Peleg, made some of the most important contributions to the theory of voting.

He made most of his career in what we now call social choice theory. Social choice theory is a branch of game theory which deals with collective decision making. This field was started by people like Condorcet and Borda in the period of the French Revolution, who were both mathematicians.

They introduced some of the most important concepts in social choice theory, like Borda Voting Count and the Condorcet Voting Method. Peleg was a very important contributor to this literature and he influenced me very much in the beginning of my career.

The other person who influenced me was my good friend, Kenneth Arrow, probably the greatest economic theorist of the 20th century.

His main contribution, which got him his Nobel Prize in 1972, is known as the Arrow Impossibility Theorem. He pointed out a very crucial difficulty that we face whenever we are trying to design a well behaved voting system. Arrow found that there is an inherent problem in achieving desirable properties for voting rules that you must compromise if you want to create such a system.

It’s a fundamental theorem that is now being taught across the world in economics, in mathematics, but also in fields such as social science and computer science. There is a lot of work being done on Arrow Theorem by people doing algorithmic game theory in computer science departments.

It’s a very lively research area to which I myself eventually managed to contribute. Back to your question, it’s mostly the people that I interacted with that made me become enthusiastic about game theory and voting theory.

It’s quite interesting that you mention Condorcet and voting research in the early days of the French Revolution. Projects like Kleros and others working on blockchain governance are, in a way, like the Federalists in the United States in the 18th century. They were trying to figure out what were the best institutions to scale democracy: what should be the best voting system in a time where there was no previous experience in designing voting systems? In the case of Kleros, we are trying to find out what is distributed justice, how it should work when there hasn’t been any previous experience in this...

Distributed justice is potentially a new area on which we didn’t put too much thinking in the past, just because the technology wasn’t available. Sometimes really big ideas come up in science because some technology is making us conscious of things that were not relevant in the past, because we couldn’t use them.

Now we have an opportunity to design a new legal system that, at its’ first steps, would only involve clearly civil cases and not criminal cases, because there is still a lot to do to put people in jail as a result of people fighting online. That stage may potentially also appear, who knows, but clearly only in the future.

These pioneering engagements in this world are very important, it’s very mind boggling and you should be very fortunate to be engaged in it.

We are really privileged to be working in such an exciting field. We know that the work we are doing now will have an impact for a very long time, because lots of people are going to build on it. What are these new technologies that make this the right time for distributed justice? Why now?

The main thing is the size, the ability to get a lot of opinions together, the crowd wisdom effect that we couldn’t get from juries in the past, the easiness of handling juries. We don’t have to get juries together in a room and lock them up until they make a decision.

We have a better way to control what kind of information we want them to know. We have a better way to affect the thing which they will be influenced by.

For example, in the current way that courts are handling cases, you hear a piece of evidence from the defendants side or from the prosecution side and the judge decides this piece of evidence was not generated legally. He would then instruct the juries not to take this piece of information into account.

This is very hard to do for the jury itself when we know that the evidence is there. With distributed justice, we can control what we want the jury to be influenced by and what not. It’s about size, it’s about the screening, a more rigorous control of information and it’s about the speed at which decisions are being made.

These three aspects have changed due to the advances in computer technology, not even blockchain. The fact that we can make this kind of decision online facilitates all these properties that we couldn’t achieve in the past.

What do you think are the main challenges this emerging field has to overcome to become a reality?

The big challenge is to convince the public and the policy makers that what we are doing is not repugnant. Many people will treat decentralized justice as repugnant, as unfair.

“You can’t let a computer decide justice”, that is a very difficult attitude that we will have to fight against.

People fear technology in all sorts of corners of life. But this fear gets stronger when we get to justice. Justice is a very elementary right, something that we don’t want to see violated. It’s very much like health, people are still very reluctant to be diagnosed by a computer.

We’ll have to convince the public and the policy makers that this technology is not only for making things faster and less expensive, but it’s also making the decisions better.

It’s also providing an outcome with a higher quality than the past. This is going to be a very difficult task, because what we are lacking with decentralized justice is the counterfactual: what would have been the decision if we did things the old way?

The other aspect is that we cannot ever know ex-post, even when we get a very smart jury, a very qualified bunch of people who exert a lot of effort at making a decision, we will never know after they decide whether they decided correctly. This is a huge obstacle to convince policy makers they should use it.

But I think gradually, with the mistakes that regular juries make and with AI kicking in and influencing other fields of life, we’ll be able to convince that we should also change the justice system.

I always say that Kleros is about building computer software, but it’s also about upgrading the mental software of what people see as justice...

The way to do it is not by going against the conventional legal system, but rather to recruit the classical justice system into this new technology. To convince judges, courts, lawyers and policy makers in governments that this is something to help the public.

Not to compete with them, but to help them implement it gradually. And eventually maybe develop some way, a hybrid system which uses the classical courts together with some sort of a decentralized component in it. This will ease things in ways of introducing it into practice.

I’ve had a lots of conversations with government officials. They do understand what decentralized justice can do for traditional justice systems. There are disputes that traditional systems cannot handle because of costs. Small claims, like disputes for a couple of hundred dollars, cannot be handled by these systems. There is no other solution than decentralized justice...

It’s not just saturation. When it gets to one thousand dollars or five thousand dollars, you ease the standard justice systems by taking some of these cases into your territory. But when it gets to one or two hundred dollars, you don’t reduce the burden on them, but you generate more justice, because these people who find themselves in disputes over a couple of hundred dollars never go into the standard court systems. It’s just too expensive to engage yourself in a case.

The outcome of this is that these people are left without justice. When the amount of money is marginal, a decentralized approach can help people enjoy their right to justice.

Before you go... would you like to become a Kleros Juror?

You can always sign up to become a juror adding your email to a mailing list. Use of our juror platform is fully decentralized of course but this lets us get in touch to notify of any pilots or real Dapp's ready for you to arbitrate on.

Join Kleros!

Join the community chat on Telegram.

Visit our website.

Follow us on Twitter.

Join our Slack for developer conversations.

Contribute on Github.