Lessons from the History of Politics for Blockchain Governance

A tour de force, Federico Ast teaches us the value of lessons from the history of politics in creating novel governance institutions for the blockchain age.

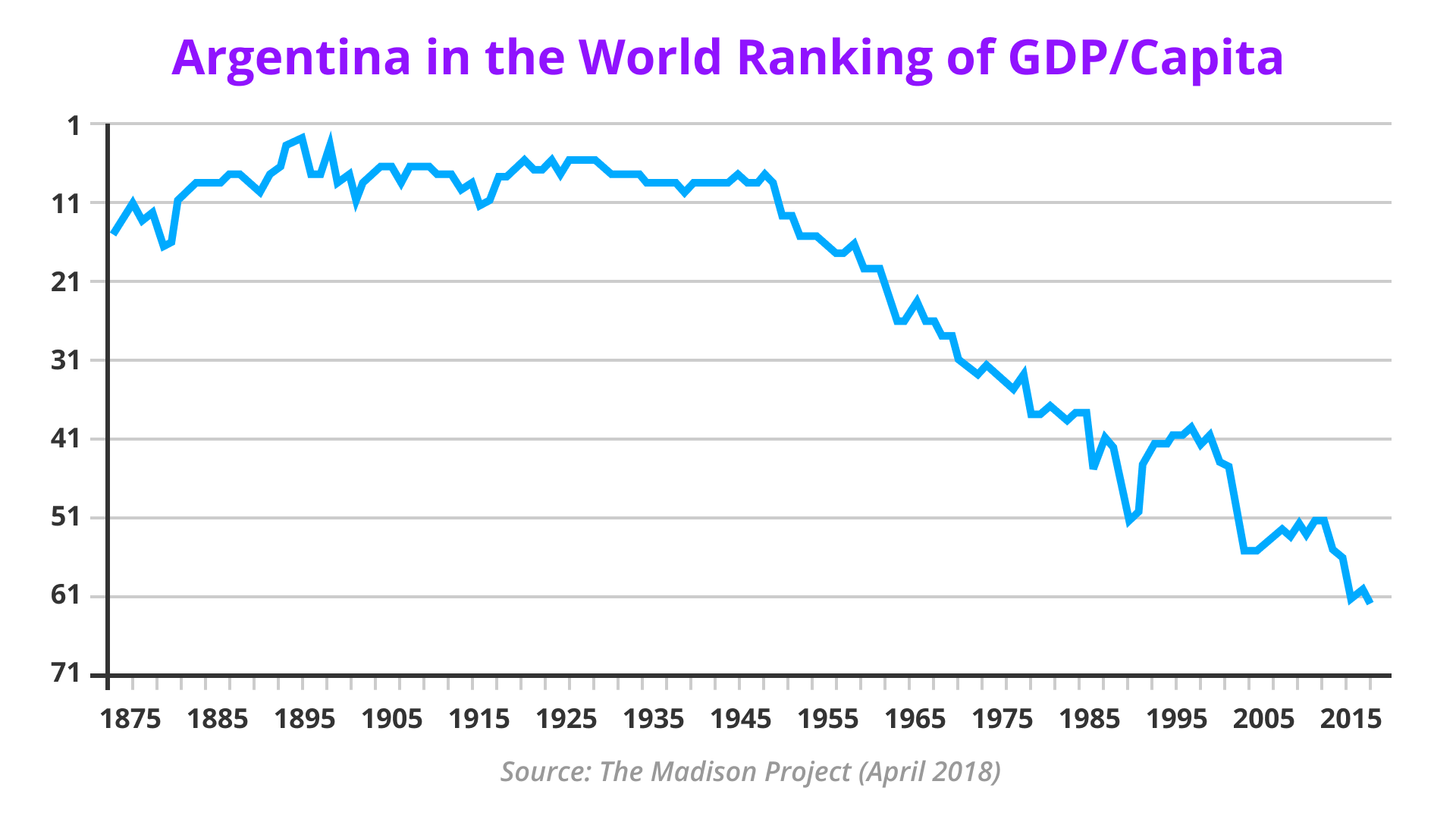

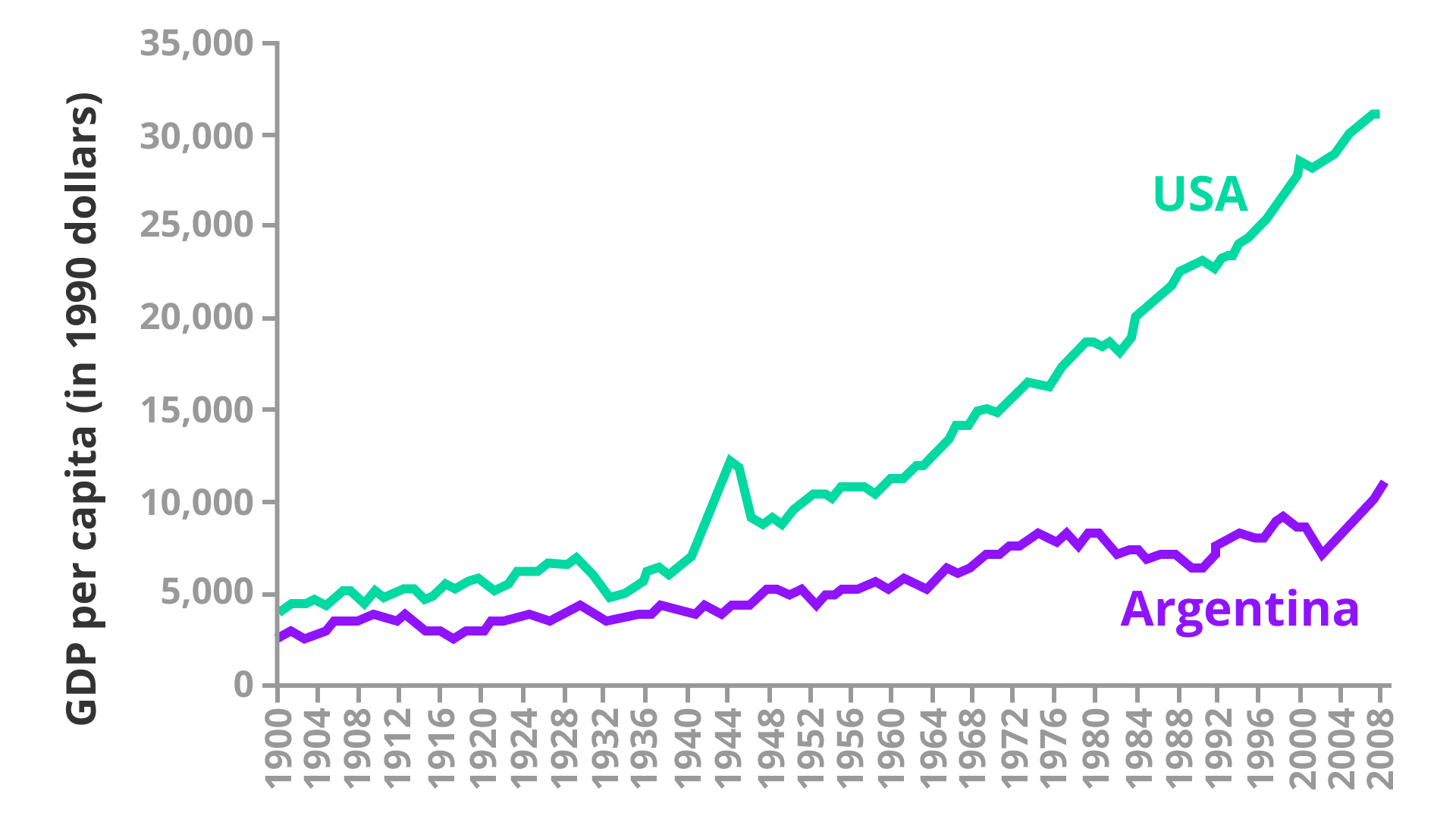

My country, Argentina, is mostly known for football and good beef. And unfortunately, for being one of the most notorious economic failures in world history.

It went from being one of the wealthiest societies in the world in the early 20th Century to just a middle income country a century later.

While I was studying economics and philosophy in the University of Buenos Aires, this sparked my interest in a specific field called institutional economics, a cross-discipline that uses insights from economics, law and social science to understand how the institutions of a society affect its economic performance.

Little did I know back then that all those learnings would become relevant in the context of DAO governance.

Governance Problems in DAOs

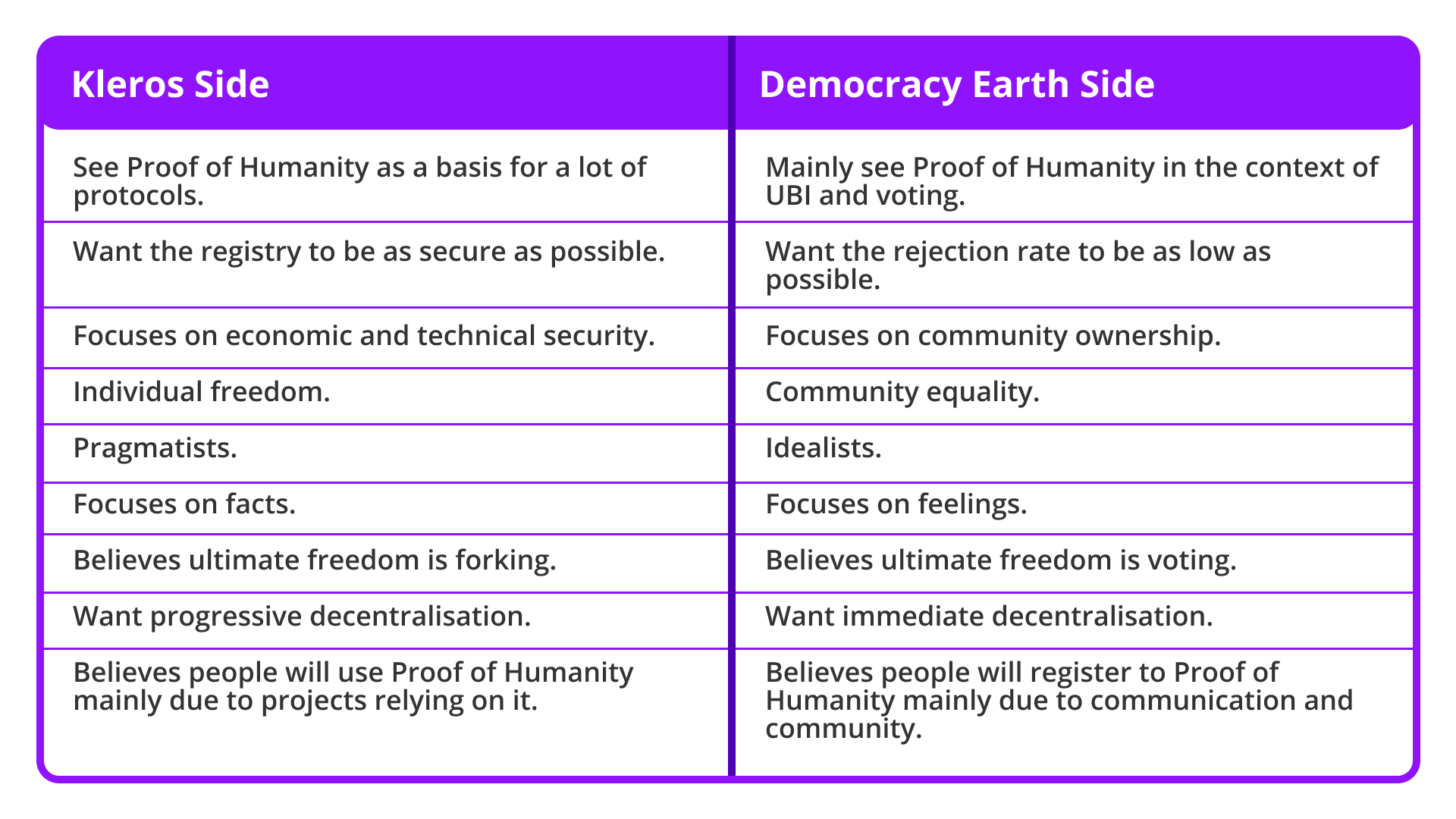

Many DAOs in the process of decentralization have suffered from acute governance dramas. Some high profile examples include MakerDAO, Aragon and Proof of Humanity.

This faces us with a reality: software developers were never trained for creating governance systems. That said, many things can be learned from the history of politics and government theory.

My goal in this article is not to provide definitive answers (which I don’t have) but just to introduce some of these ideas in the discussions of DAO governance.

“History never repeats itself, but it rhymes”. Mark Twain.

Why Does Decentralization Matter?

In the Middle Ages, Europe was a fragmented territory where many small kingdoms frequently fought each other. Feudal Europe was quite a decentralized world.

In 1648, the Peace of Westphalia put an end to the ravaging Thirty Year's War and many of those small kingdoms consolidated into nation states governed by absolute monarchies.

A few years later, in 1651, English philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote one of the most influential books in the history of politics: Leviathan. This book defended power centralization as a way to bring peace. Peace with which prosperity could ensue.

Hobbes argued that the state of nature of man is a war of all against all. Without political organization, life would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” A strong, centralized government, Hobbes argued, is necessary to avoid the situation of war. By fostering peace and order, it enables citizens to focus on work and productive activities, which in turn enables economic prosperity.

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson are two of the most renowned institutional economists of our time. Their studies focus on the impact of institutions on economic growth. They co-authored two highly influential books, titled "Why Nations Fail" and "The Narrow Corridor".

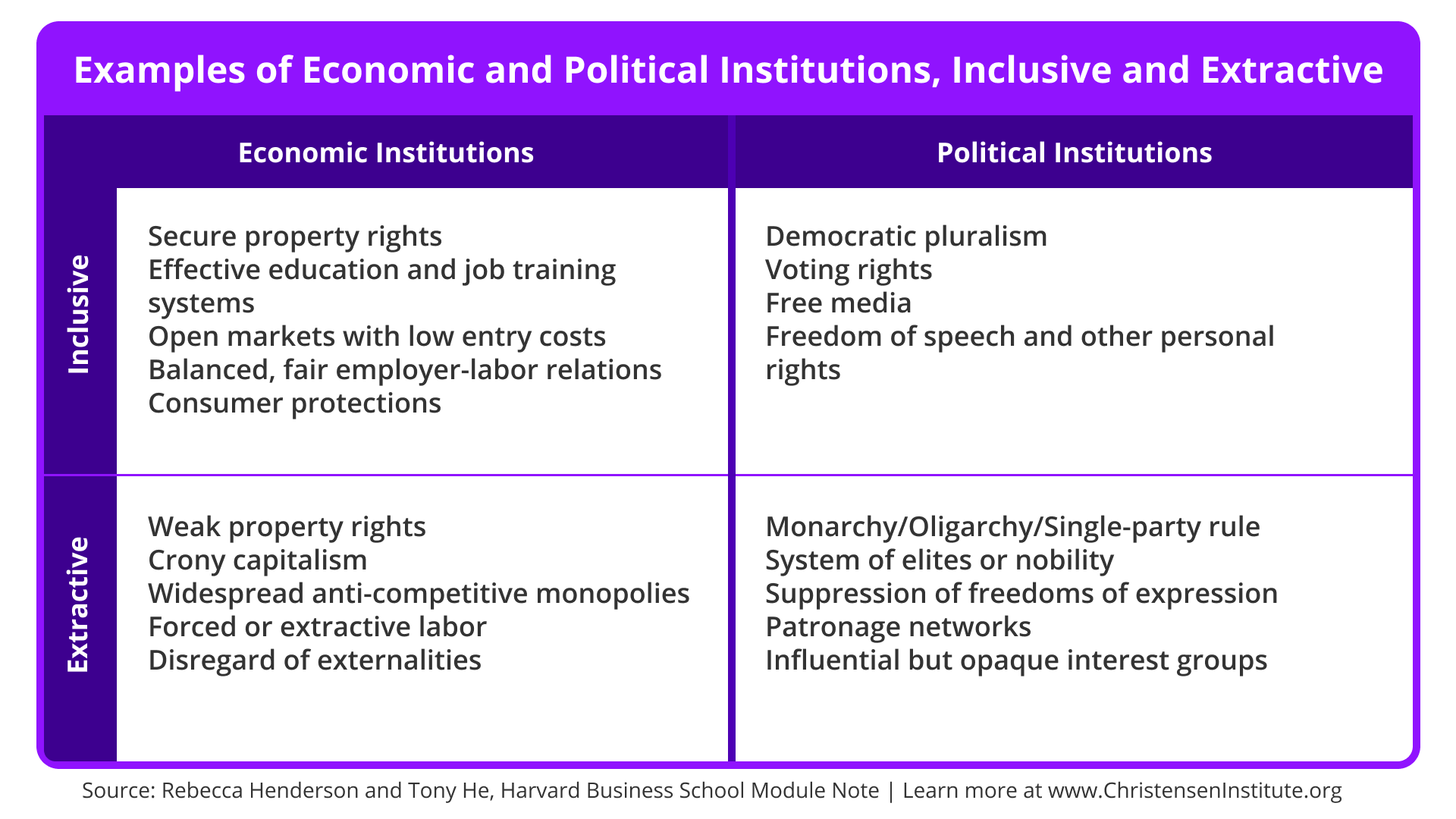

Their analysis makes a distinction between extractive and inclusive institutions.

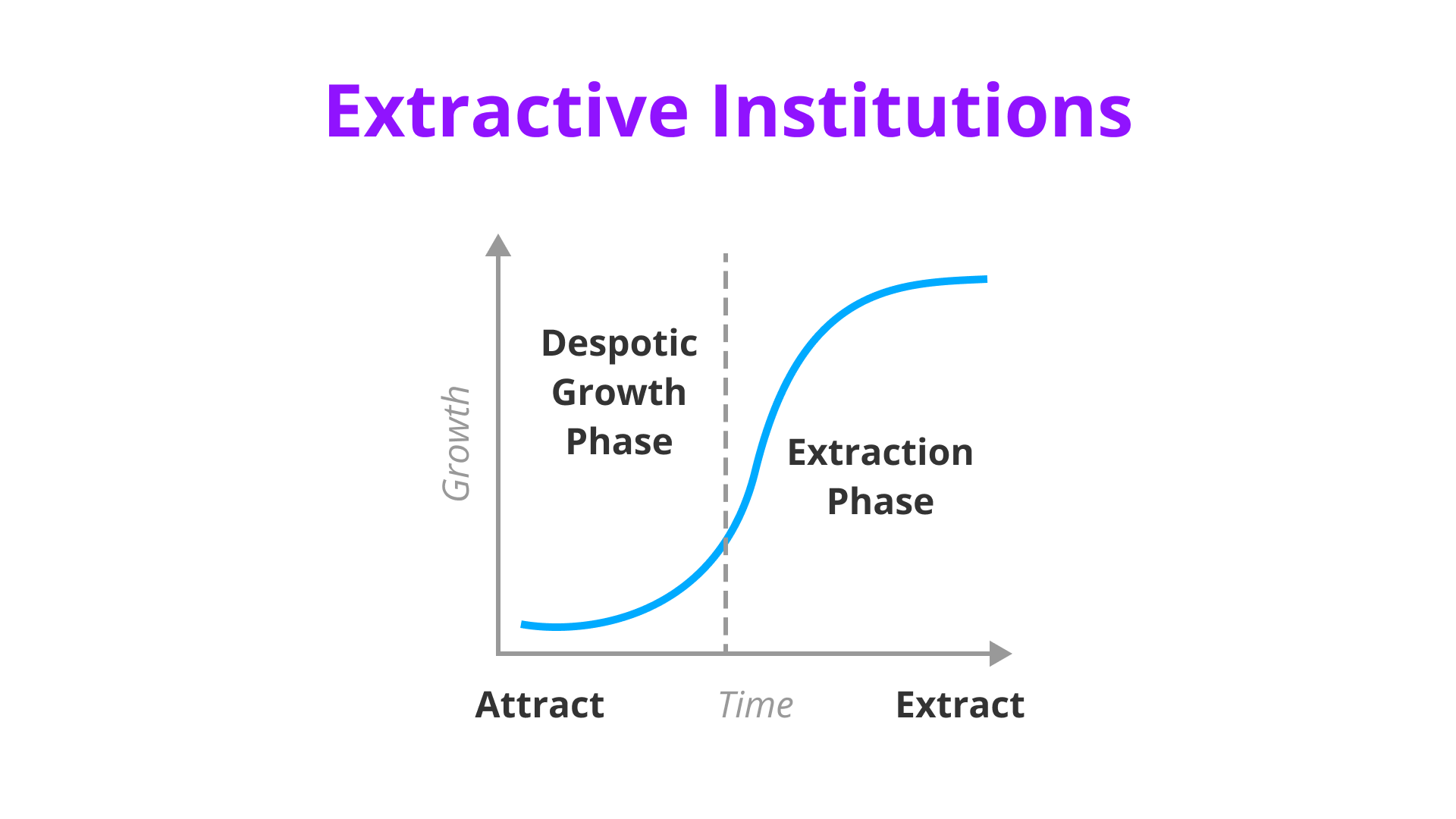

Centralization is important to bring peace and enable economic growth. But there’s a limit. As a society becomes wealthier, the ruler becomes increasingly tempted to impose taxes on the citizens. Absolute monarchies may have their benefits initially, but if they persist for too long, they give rise to extractive institutions that only serve the interests of a small elite.

The early days of the Internet were a bit like feudalism. It was a bunch of small and scattered little websites and blogs with a decentralized structure of authority and no central body of control of the Internet as a whole. Communities were like fragmented territories with their own rules, platforms, and norms. These communities often operated independently, fostering their own subcultures and identities.

Eventually, this consolidated into the walled gardens of the big tech companies. These companies were great to help the growth of the internet and spreading it to every corner of the world - but there’s a catch.

We can observe Web 2.0 platforms as absolute monarchies in this context, where a small elite holds power.

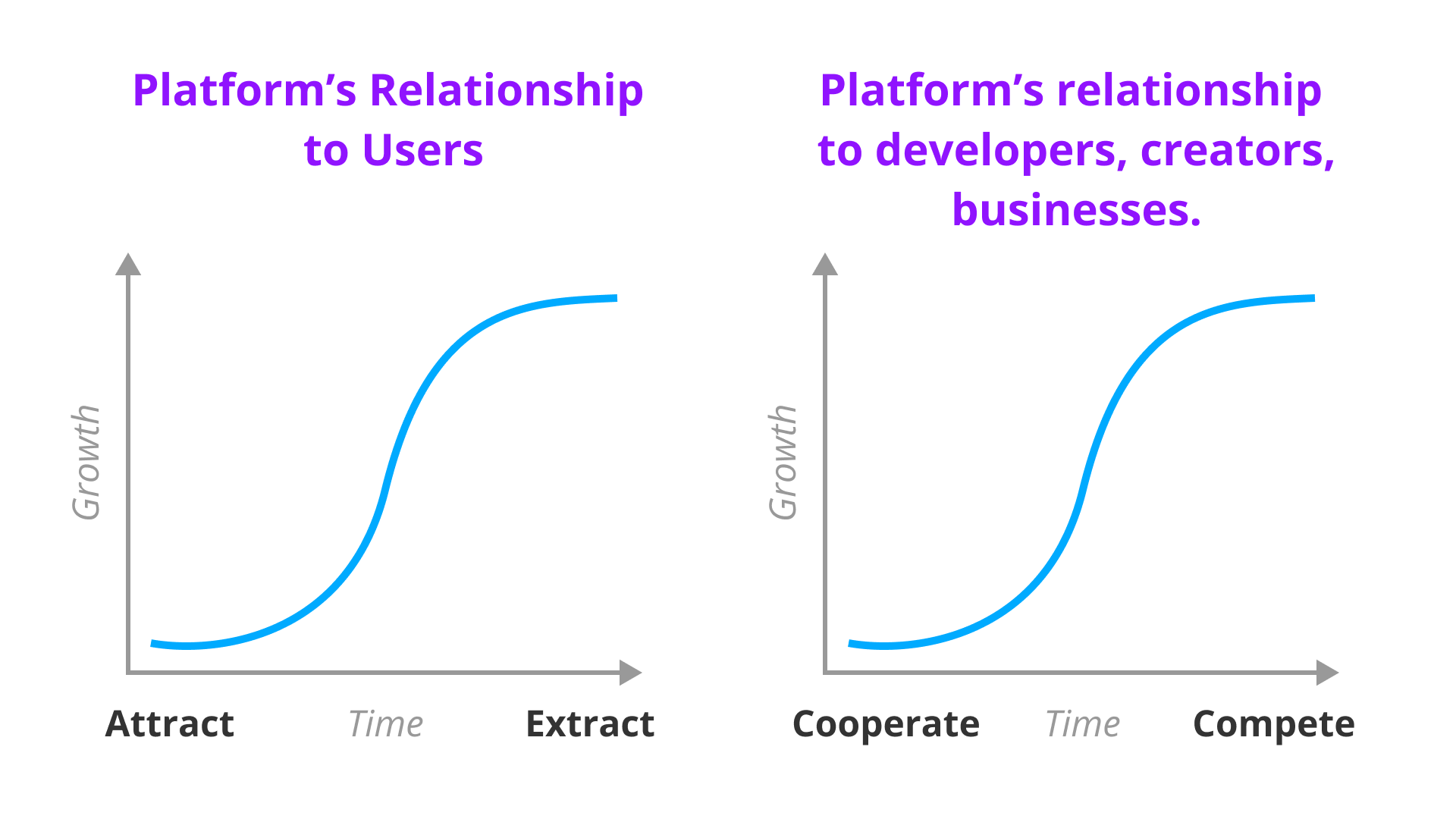

In a famous article titled "Why Decentralization Matters", Chris Dixon elucidates the economics of Web 2.0 platforms, which bear striking resemblance to Acemoglu and Robinson's extractive institutions.

First, they begin by attracting users to create network effects. Once they have achieved a critical mass, they proceed to extract resources from their users and from everyone who has built on their ecosystem.

The idea of credible neutrality is the answer to extractive institutions in the online realm by implementing mechanisms for accountability, the rule of law, and popular control. This leads to inclusive institutions where the economy works for everybody, ultimately resulting in sustained economic growth.

This is why we Web3. It’s the way to create rule of law online and to build digital inclusive institutions.

What's Cool About Democracy?

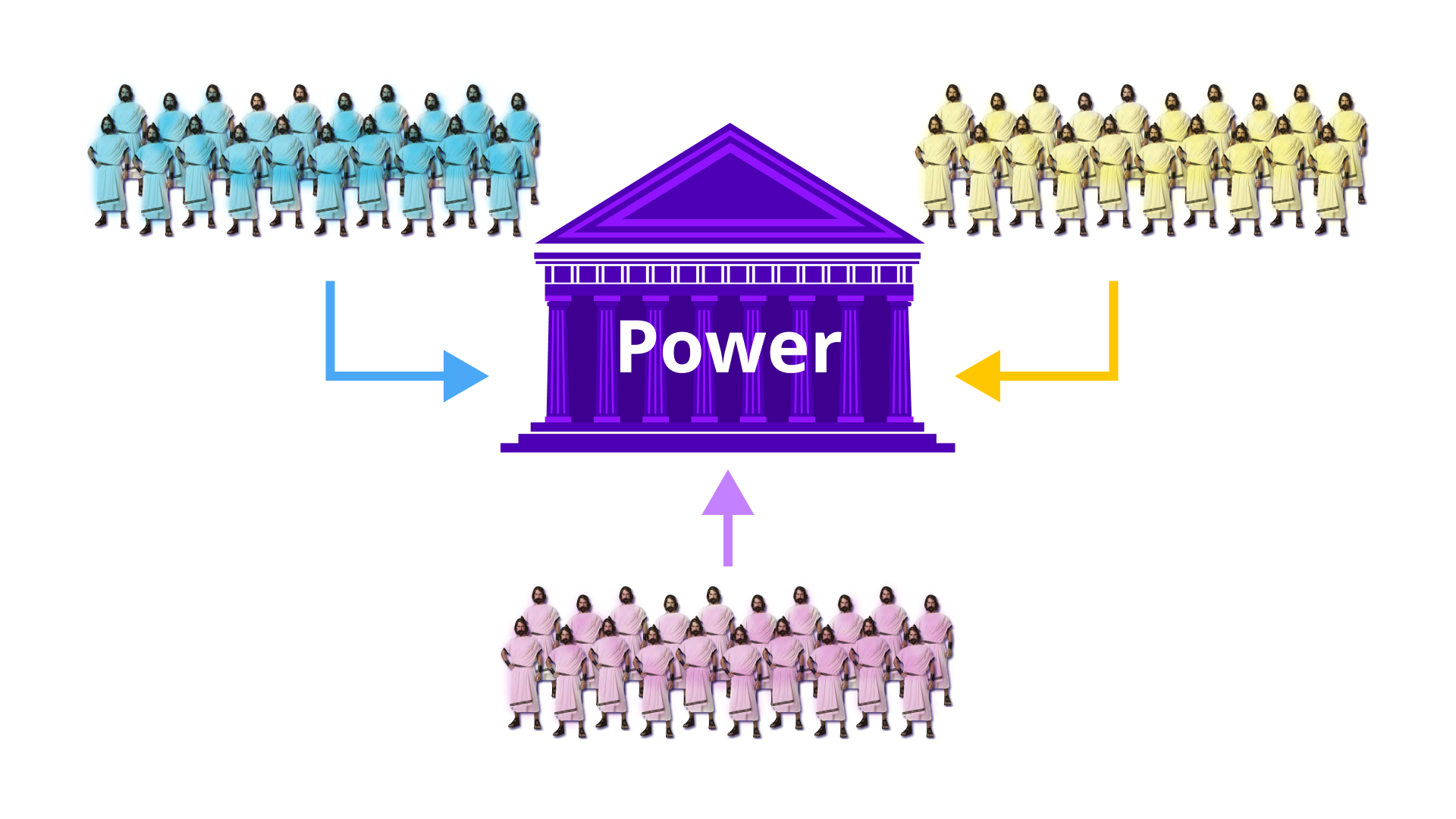

Democracy is important because giving people a voice and a vote in decisions is a source of legitimacy. Also, as Aristotle argued, higher diversity leads to better decisions. Finally, popular control helps avoid the extraction dynamics described by Acemoglu and Robinson.

Many attempts to build DAOs have failed because of a flaw we could call "democratic fetishism". We could define it in the following way:

“Hey, bros. Let’s take power in our hands and vote about everything in our DAO.”

An idealized version of democracy where everyone should be able to vote about any topic.

April 19, 2021. The birth of the first democratic DAO. https://t.co/OtsG6sq5LE

— Federico Ast (@federicoast) April 19, 2021

We ourselves were victims of this democratic Fetishism when we launched Proof of Humanity. We called it the first democratic DAO which gave every user participation rights under the model of 1-person-1-vote.

But this didn't work…for predictable reasons. When they met to draft the Constitution, the founding fathers of the US were very aware of the perils of democracy.

“Such democracies (...) have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths”. James Madison.

The Problem of Knowledge

Decision making needs specialized knowledge and time to analyze the issues. And few people possess the knowledge and have the time.

In his Republic (488a–489d), Plato presents the famous allegory of the "Ship of State" to explain the dangers of majority rule. If sailors without proper knowledge of seafaring were allowed to choose the captain, they are very likely to make a wrong decision and the ship might sink.

Plato believed that the main problem of democracy was that people were manipulated by orators in the theatre. The regime could degenerate to a theatrocracy.

Which in the world of Web3 we could call Twittocracy.

The people getting the more delegations in DAOs are typically crypto Twitter celebrities. It’s unclear that these people have the right skills and knowledge to make decisions in all the DAOs where they participate.

John Stuart Mill was a 19th Century intellectual and one of the main figures in classical liberalism. He was one of the main defenders of universal suffrage. However, people with higher education should be given more votes, as these people are less likely to be manipulated by demagogues.

The Danger of Factions

“By a faction, I understand a number of citizens (...) who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to (...) the aggregate interests of the community”.

- James Madison

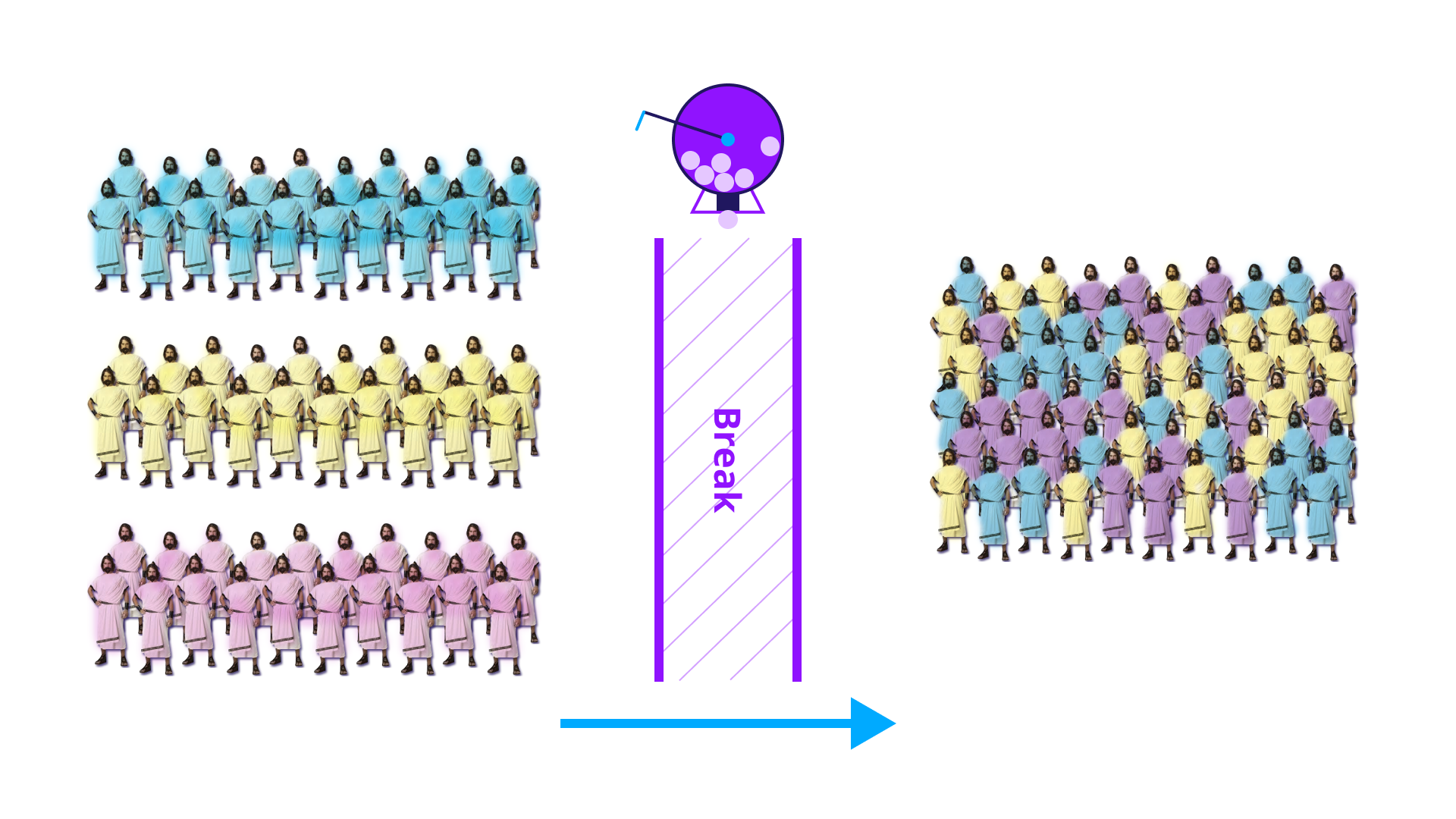

This is the process of citizens organizing to make decisions based more on their private interests rather than common good. When a faction becomes very strong, it can end up crushing minorities. For example, a religious majority persecuting a minority, or even a majority of have nots avariciously expropriating a vulnerable minority.

How to make good decisions and avoid the dangers of factions while at the same time preserving the spirit of popular government?

The founding fathers rejected the ancient model of democracy and relied on political representation instead, associating representation not with democracy but with republicanism.

The idea was that public views would be passed through the filtering device of a chosen body of citizens able to better discern the interests of the country.

But what if people choose the wrong representatives? What if they were seduced by demagogues or populistic leaders?

The Danger of Demagogues

Demagogues can be recognized as they present themselves as men or women of the “pure common people”, opposed to the “corrupt elite”. They seek to create a plebiscitary democracy where the majority decides everything.

In order to defend against demagogues, one can address their rants with facts and arguments. The Athenians developed an institution called ostracism to fight the dangers of demagoguery. Every year, Athenian citizens would vote if they saw some politician becoming too popular and potentially becoming threatening for the system. Then they held a vote with a token called ostraka. If you were selected by the vote, you were banned from politics for 10 years.

Suggested readings:

- "Populism, a very short introduction" by Cas Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser.

- "The Demagogue's Playbook" by Eric Posner.

Separation of Powers

If one power misbehaves, then the other branches of government are there to control it. In essence, a system of checks and balances to prevent accumulation of power into demagogue leaders.

Checks and balances, rule of law and protection of minority rights.

Decentralized Courts in Blockchain Governance.

Key question here to ask would be: how can we implement separation of powers in the DAO?

Deriving from this question, another one is immediately upon us: how can powers in a DAO be separated so there's no risk of too much power being accumulated in the hands of a demagogue?

Lotteries: the Road Not Taken

Let me mention one solution that people don't know much about but that was very important in the past: lotteries.

Ancient democracies saw elections as an aristocratic device. People who have the time and skills to be elected are typically the elites. This naturally results in a political regime controlled by the wealthy.

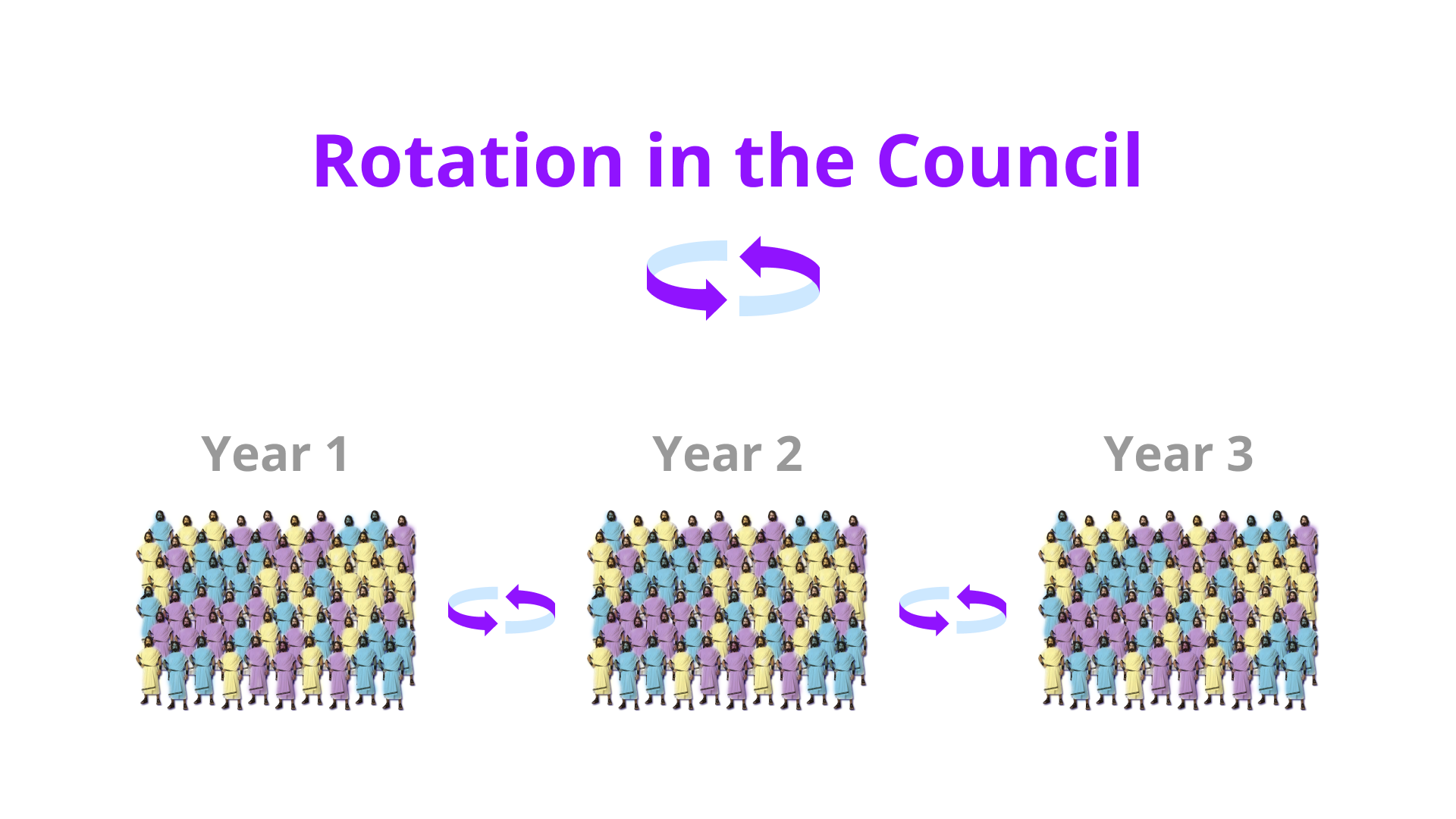

To avoid the oligarchic effect of elections, classical republics assigned most magistracies by citizen-wide lotteries and observed frequent rotation.

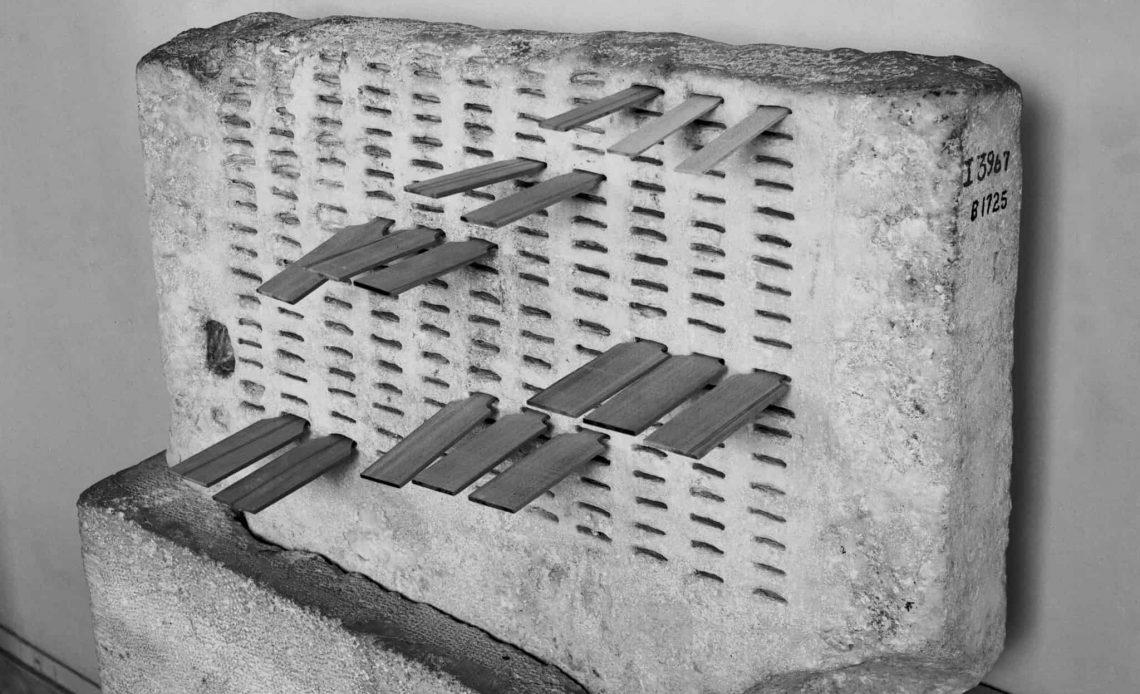

Athenians had developed a very specific method for sortition. It relied on the pinakion, an ID token that every citizen had in ancient Greece. They put the pinakion into the slots of this lottery machine called Kleroterion. An official would come and throw black and white balls into a tube on the side of the kleroterion. If you had a white dice on your row, you were chosen for office. If not, you were dismissed.

Random selection and rotation summarized the core idea of ancient republics: to rule and being ruled in turns.

Some books to learn more about the use of sortition:

- "The Luck of the Draw: The Role of Lotteries in Decision Making" by Peter Stone.

- "The Political Potential of Sortition: A study of the random selection of citizens for public office" by Oliver Dowlen.

- "Open Democracy" by Helene Landemore.

A question to ask here is a simple one - is it possible to introduce lotteries in some procedures?

Is There a Perfect Constitution?

So, it's easy right? Let's just wait for someone to come up with a good constitution and then implement it in our DAO. But not so fast…it doesn't work like that. This raises the question: is there a perfect model of constitution that all societies should adopt?

This was a hotly debated topic once upon a time. On one side of the debate, there was English philosopher Jeremy Bentham. In 1823, he published a manifesto titled "Leading Principles of a Constitutional Code for any State".

“The great outlines which require to be drawn, will be found to be the same for every territory, for every race and for every time”.

- Jeremy Bentham.

The goal was to create a perfect liberal constitution and then have it spread all over the world.

On the other side, French philosopher Baron de Montesquieu. In his very influential book “The Spirit of Laws”, he contended that a country’s laws should be drafted in accordance to its specific culture and geography.

In 1808, Napoleon invades Spain. As the king of Spain wasn’t around, main colonies from the Americas declared independence.

Many decided to just copy the US Constitution which had been passed about 30 years ago and was considered a success. It’s estimated that about ⅔ of the Argentinian Constitution is basically a copy of the US one.

So with Argentina's adoption of large parts of the US Constitution, the trajectories of the countries were very different. Why do two countries with very similar formal institutions have such different results?

The Social and Cultural Background of Democracy

Many thinkers have argued that the social and cultural background of a community are very important to determine what form of government they can sustain and how it will perform.

A critical element is how wealth is distributed in a community.

A Frenchman called Alexis de Tocqueville travelled to the United States in the early 19th century to learn more about how democracy worked there and writes his famous book “Democracy in America”.

In that book he argued that America was a middle class society with a highly egalitarian wealth distribution. A society of small owners which resulted in a good distribution of political power.

In South America, ownership of the land was heavily concentrated in a few families. And this heavily concentrated economic power resulted in a heavily concentrated political power.

Wealth concentration usually leads to concentration in political power.

“No citizen be so rich that he can buy another, and none so poor that is compelled to sell himself”.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

It’s impossible to set up a republic without some degree of economic equality.

There is a blog post called “The Original Sin” by Chris Burniske where he argues that too much concentration of tokens in the early days of a project might result in bad decision making dynamics in the long run. When people in the community have ownership, they have a stake in the future and this creates an incentive to think about the common good.

So, how does wealth distribution affect political dynamics? How can distribution be improved?

Of course, there is no need don’t need to create a socialist revolution.

Machiavelli was a thinker and politician who lived in Renaissance Florence. People know Machiavelli from his work "The Prince", a number of ruthless lessons for the use of power. A manual for Frank Underwood, if you will.

But they fail to appreciate that he was actually a republican advocating for more popular government in his city of Florence which he explains in his book “Discourses on Livy”.

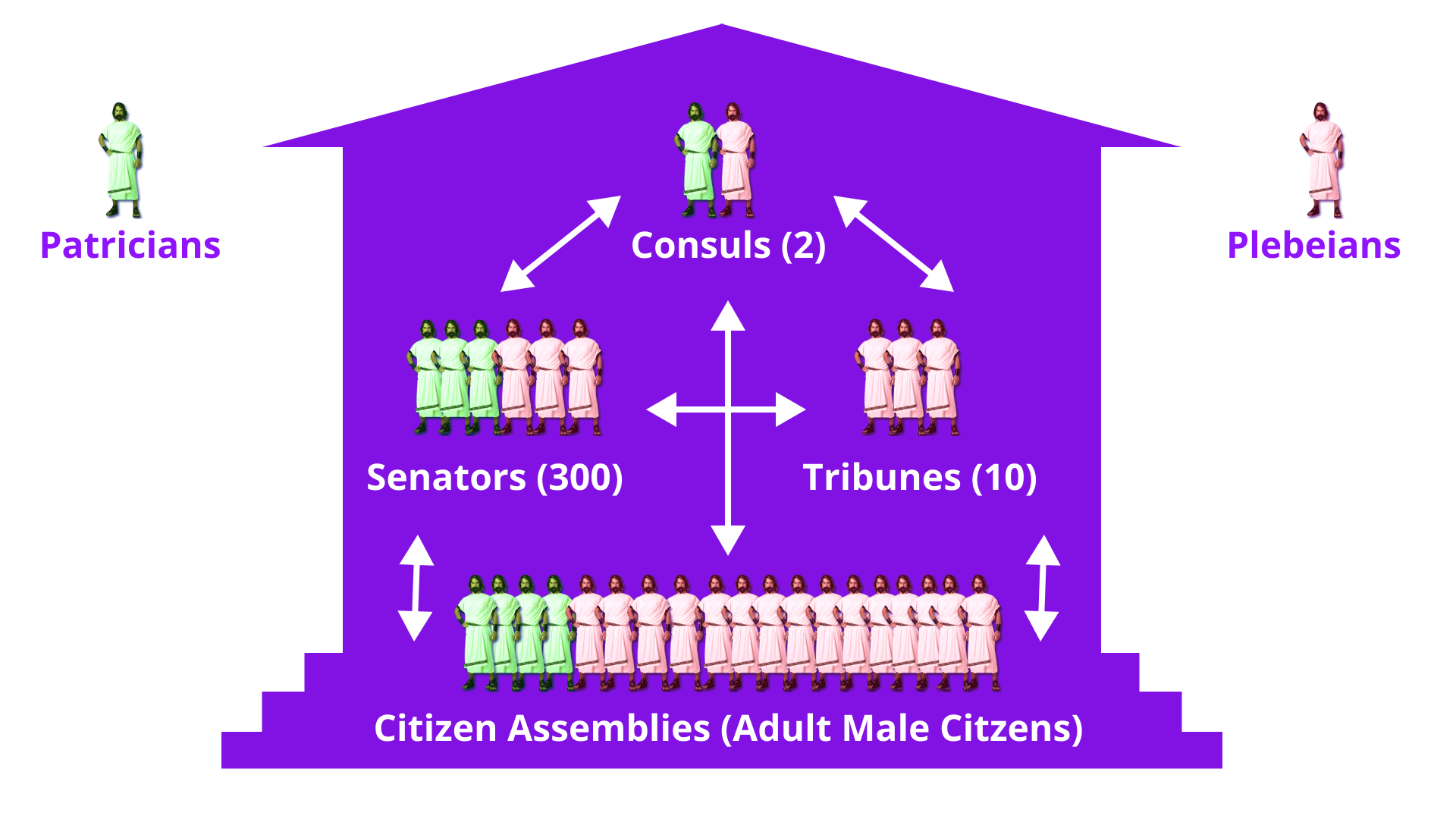

In this book he advocated for a very old institution from the Roman republic called the tribunes of the pleb. 10 plebeians were voted from the lower classes, people without any property, and they had some veto power against the elite. This helped reach a better balance of power.

Two books to learn about the republican ideas of Machiavelli are "Machiavellian Democracy" and "The Machiavellian Moment".

Getting the Government Right

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary”.

- James Madison.

“Ambition must be made to counteract ambition”.

- James Madison.

How do we mitigate the power of whales? Does good governance come from good laws or good men?

In the world of blockchain, the equivalent to getting the government right is getting the mechanism design right. A mechanism that cannot be gamed by malicious actors.

Rely on Incentives, Not On Moral Virtue of Agents

What about morality and political culture?

The book “How Democracies Die” tells us that the success of the United States has less to do with the structure of its constitution than people usually think. The success had more to do with a very strong political culture. Even if the constitution was far from perfect it still worked because the society had a high level of civility.

There's the unwritten rule of treating political adversaries as equals with dignity and respect.

Self restraint and underutilization of one's power. Not to cede to temptations of packing the supreme court even if there are no explicit formal rules against this. It's respecting the spirit of the law. For example, before the 1950s, no US president looked for more than one reelection even if there wasn't an explicit rule against. Forbearance were soft guardrails for democracy.

In our experience, one of the reasons for the failure of the Proof of Humanity DAO was that different factions had completely different ways to see the world and they lacked some basic civility to work together. There never was a culture of collaboration.

In the crypto world, a very interesting debate was triggered by Nathan Schneider’s paper on “Cryptoeconomics as a limitation on governance” and Vitalik's answer to it, titled “On Nathan Schneider on the limits of cryptoeconomics”.

How can we create a culture of civility and collaboration?

Do we want a community of degens who are there just for a quick buck? Or we want people who are in the community because they believe in the vision?

Can we improve the political culture by education? Or even by religion?

Religion. From the Latin Religare. “To tie”, “Relier”.

Inculcating civic virtue through festivals, public instruction, symbols and ceremonies. A religion based not on the supernatural but on moral values.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Many scholars argued that ultimately the cohesion of a society and the effectiveness of a government for collective action relied on religious grounds. But not a supernatural religion. A civic religion that helped socialize people into cooperation.

Maybe the philosopher who expressed this in the best way was Ibn Khaldun, the greatest political philosopher you’ve never heard of. We're witnessing a revival in recent years as some heavy hitters such as Ray Dalio, Peter Turchin and Balajis cite his work.

He wrote this extremely interesting book called "The Muqaddimah" which is an introduction to history. A book that comes highly endorsed by many famous people including Mark Zuckerberg.

Assabiyah. Social solidarity, bonds that exist between members of a social group. These bonds are critical for social cooperation and coordinating collective action.

Conclusion

DAOs are an opportunity to rethink governance from the first principles and there's lots to be learned from the history of political ideas and collaboration with cross-discipline teams

Let's experiment!

“Study history. In history lies all the secrets of statecraft.”

- Winston Churchill.

Essential Readings

Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, John Jay. The Federalist Papers.

Alexis De Tocqueville. "Democracy in America".

Aristotle. "Politics".

Baron de Montesquieu. The Spirit of Laws.

Cary Nederman, “Civic Humanism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Cas Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser. "Populism, a very short introduction".

Chris Burniske. “The Original Sin”.

Chris Dixon. Why Decentralization Matters.

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson. Why Nations Fail. Crown Business.

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson. The Narrow Corridor.

Eric Brown. Plato’s Ethics and Politics in The Republic. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Eric Posner. "The Demagogue's Playbook".

Federico Ast. The Revival of Demarchy: Kleros as a Political Technology.

Frank Lovett, “Republicanism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Fred Miller. Aristotle’s Political Theory. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

James Crimmins, “Jeremy Bentham”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The Social Contract.

Jeremy Waldron, “Rule of Law”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Jimmy Ragosa. A Case for Separation of Powers in DAOs.

Jimmy Ragosa. Building an Independent Judiciary for Sovereign DAOs.

John P. McCormick. Machiavellian Democracy.

J.G.A. Pocock. The Machiavellian Moment.

John Stuart Mill. Considerations on Representative Government.

Helene Landemore. "Open Democracy".

Ibn Khaldun. Muqaddimah.

Nathan Schneider. Cryptoeconomics as a limitation on governance.

Oliver Dowlen. "The Political Potential of Sortition: A study of the random selection of citizens for public office".

Peter Stone. "The Luck of the Draw: The Role of Lotteries in Decision Making".

Plato. Republic.

Plato. Laws.

Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die.

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.

Tom Christiano and Sameer Bajaj, “Democracy”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Vitalik Buterin. Credible Neutrality As A Guiding Principle.

Vitalik Buterin. “On Nathan Schneider on the limits of cryptoeconomics”.